Sunday Poster Session

Category: IBD

P1046 - Does BMI Influence Anti-TNF Treatment Response in IBD? A Longitudinal Analysis in Puerto Rican Patients

Sunday, October 26, 2025

3:30 PM - 7:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

William Larsen-Alemany, BS

UPR Medical Sciences Campus, Ponce Health Sciences University

Guaynabo, PR

Presenting Author(s)

William Larsen-Alemany, BS1, Patricia Figueroa-Rodriguez, BS2, Claudia P.. Amaya-Ardila, 2, Esther A. Torres, MD3

1UPR Medical Sciences Campus, Ponce Health Sciences University, Guaynabo, Puerto Rico; 2University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus, San Juan, Puerto Rico; 3University of Puerto Rico School of Medicone, San Juan, Puerto Rico

Introduction: Studies investigating the relationship between BMI and anti-TNF treatment response (TR) in patients with IBD have yielded conflicting results, with some proposing that higher BMIs are associated with treatment failure while others have reported that there is no association between BMI and TR. We aimed to evaluate the relationship between BMI categories and anti-TNF TR in patients from the UPR Registry of IBD.

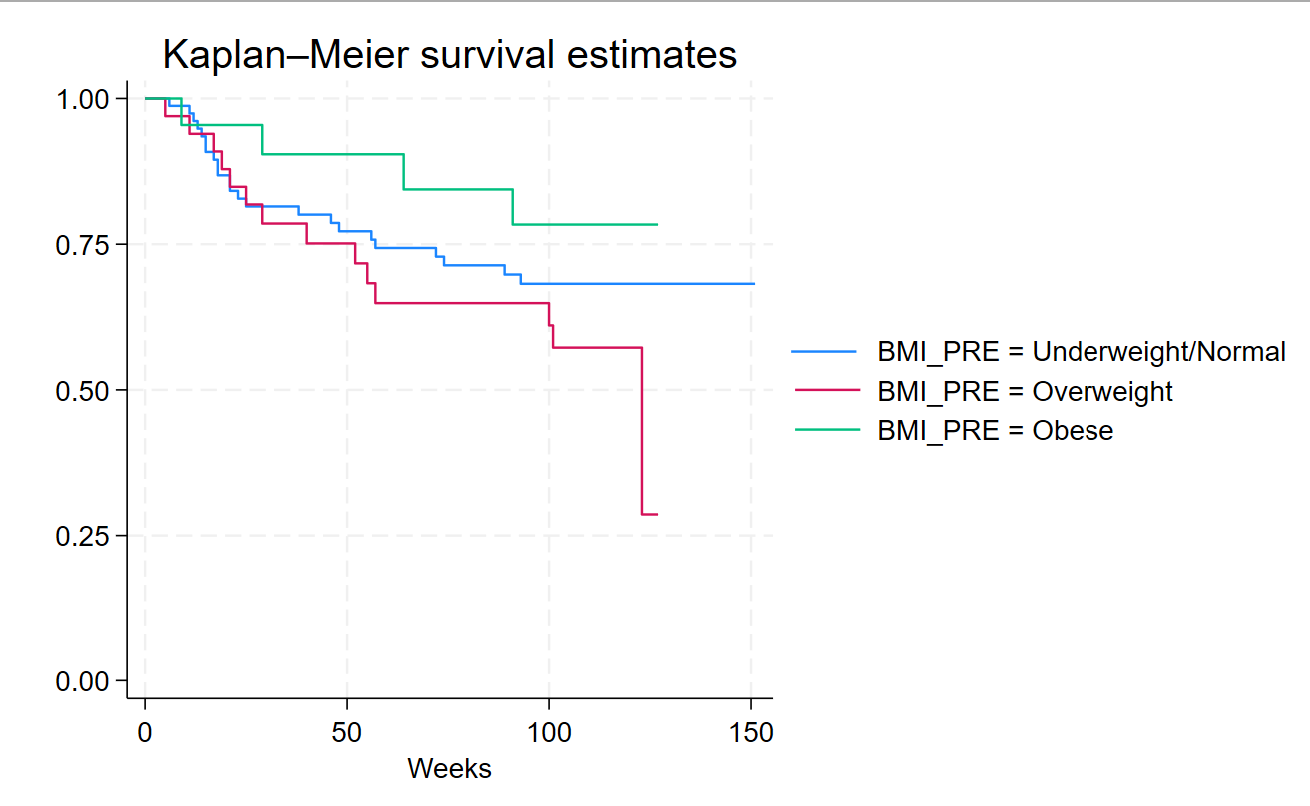

Methods: A cohort of biologic-naïve patients from 2000-2020 was selected. Patients were followed up for 12-24 months using electronic health records to evaluate TR: treatment failure (TF), sustained response (SR), or loss to follow-up. Univariate analysis was performed to describe demographics and IBD-characteristics according to TR with reported p-values. A Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival analysis based on time to TF and hazard ratios (HR) with the underweight/normal group as reference was performed. Statistical significance is set at p < 0.05. The study is approved by MSC-IRB.

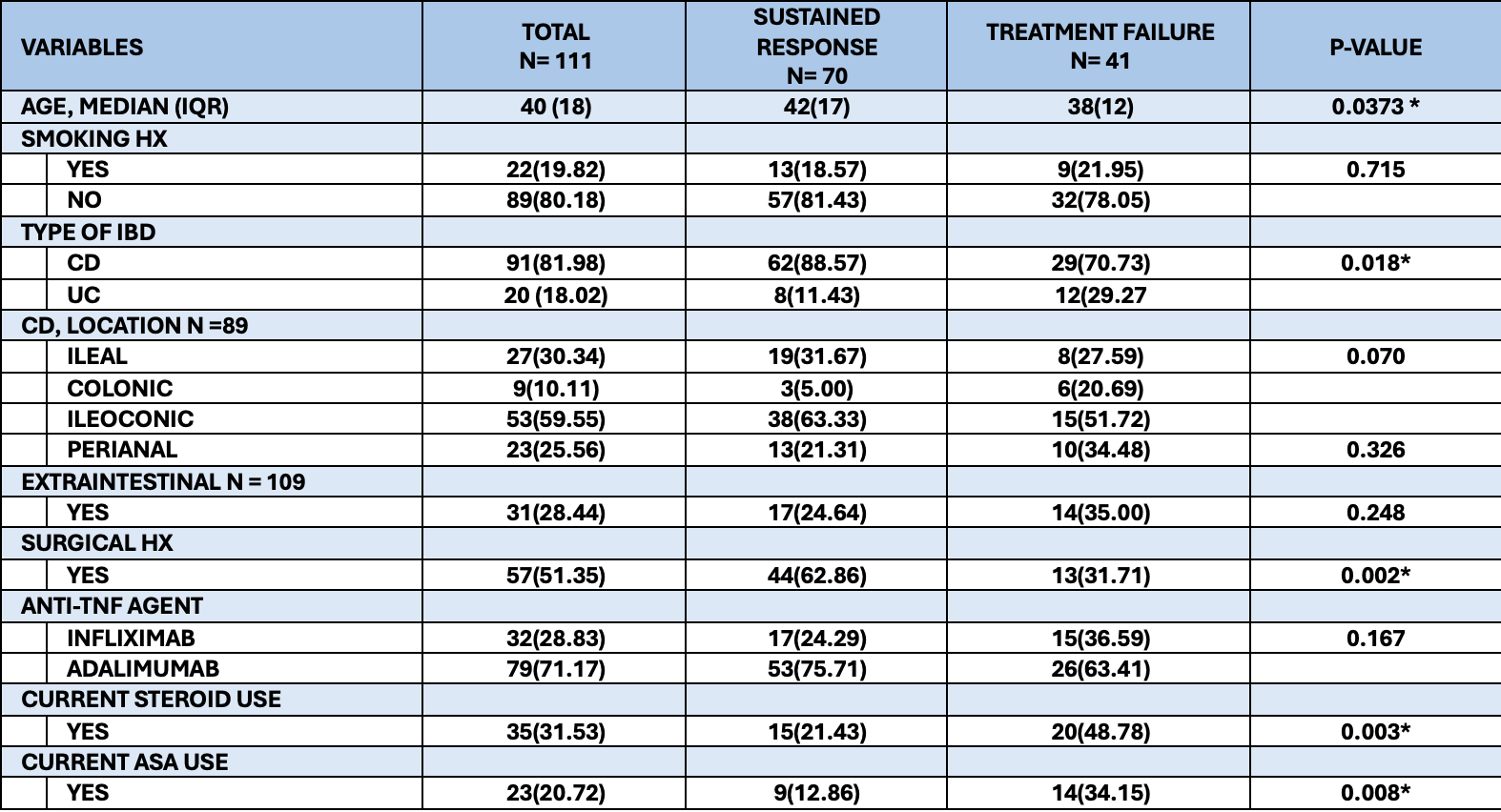

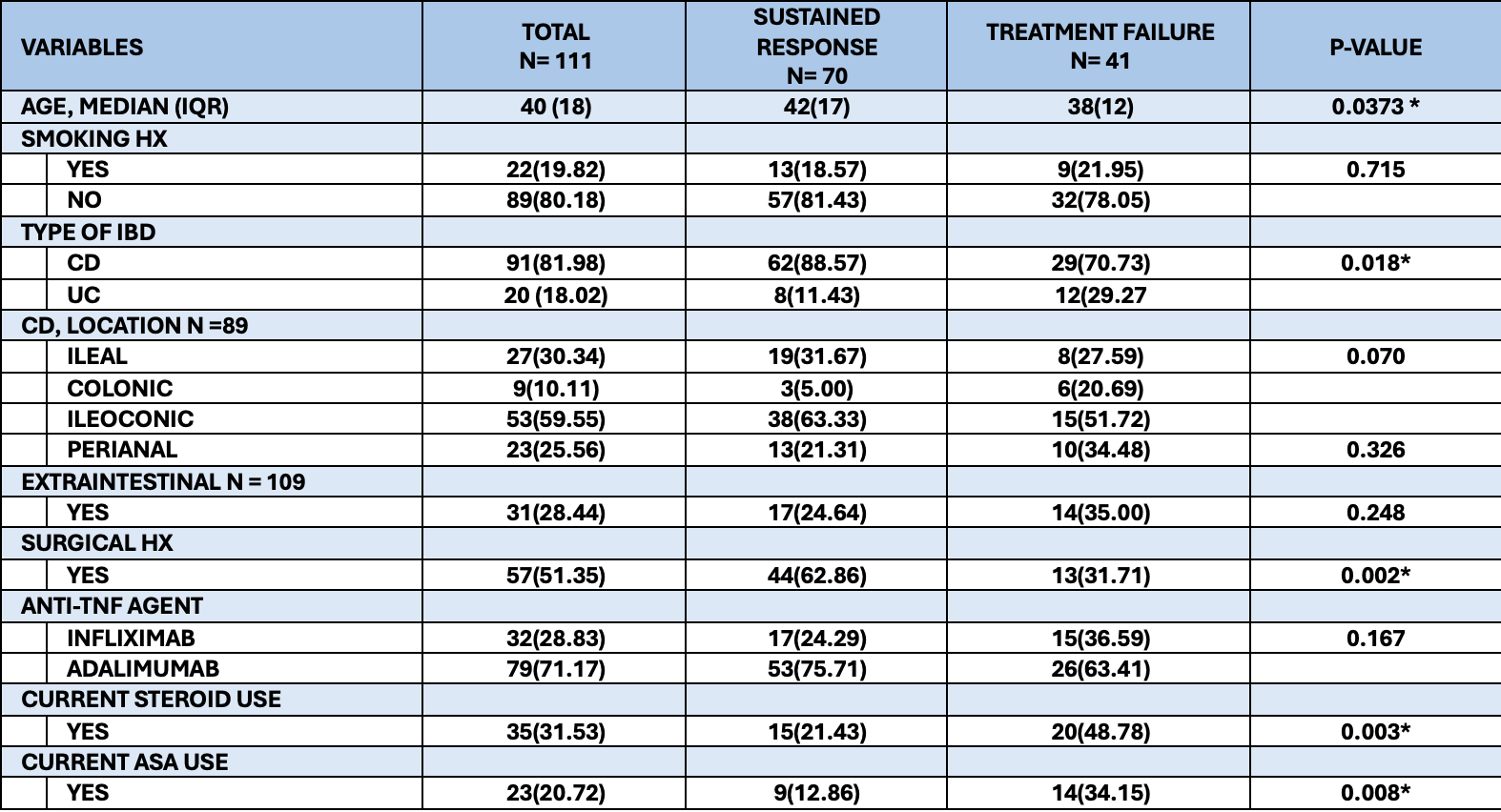

Results: 136 patients were included for TR analysis, 111 had CD and 25 UC. 79 were underweight/normal weight, 34 overweight and 23 obese. 25 were lost to follow-up, 41 had TF while 70 had SR. Significant differences between TF and SR were observed with age, type of IBD, surgical history, current steroid use and current ASA use (p< 0.05); marginal significance was seen with CD location (p=0.070). Concurrent ASA use (aHR 2.7, p = 0.018), EIM (aHR 1.4, p = 0.073), concurrent steroid use (aHR 2.5, p = 0.096), perianal disease (aHR 1.7, p = 0.331), ileal vs. ileocolonic (aHR 0.96, p = 0.112) were associated with a higher risk of TF. Regression analysis for TR yielded HR of 1.4679 (p=0.258) for overweight and 0.5918 (p=0.333) for obese compared to the normal/underweight group, showing no statistical significance between BMI and time to TF (p >0.05).

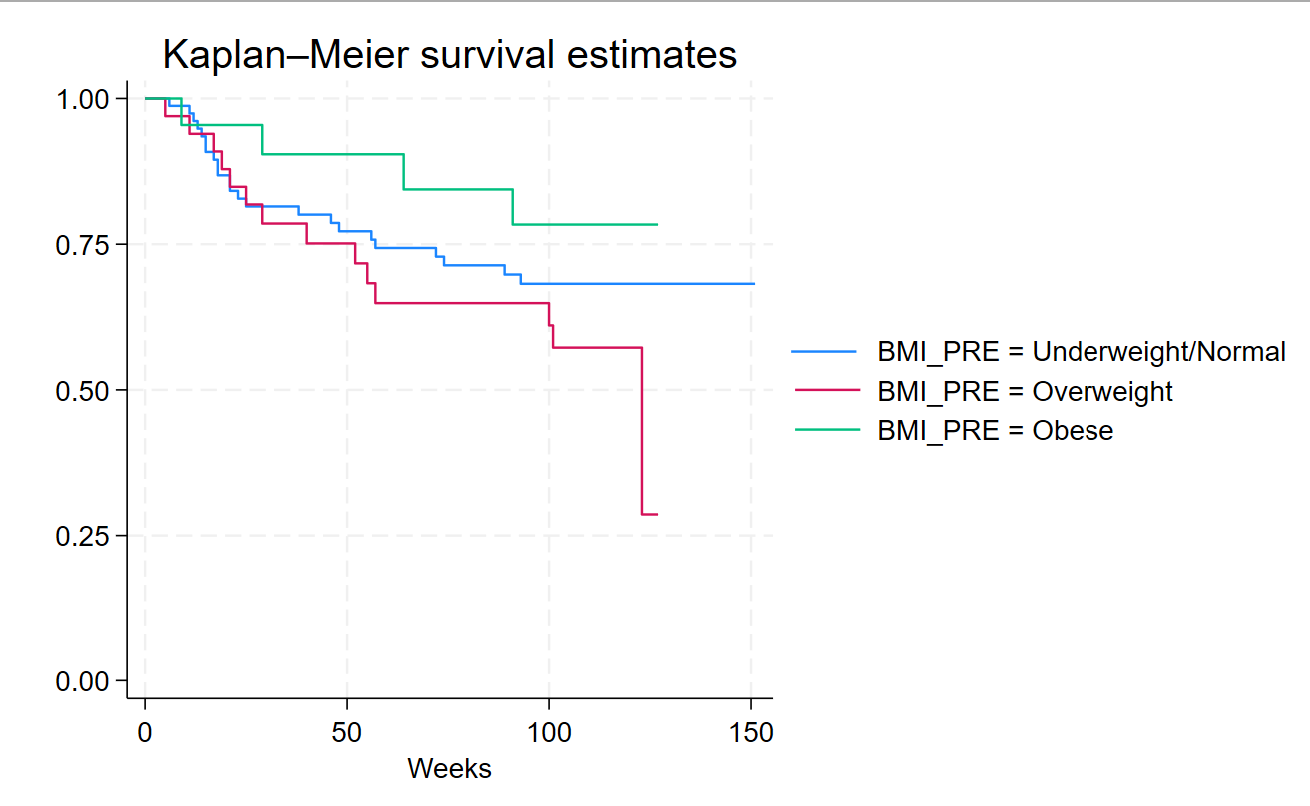

Discussion: No overall association between BMI and time to TF was found. The KM curve suggests a slightly higher risk of TF for the overweight group and a potential protective effect for the obese group compared to the underweight/normal group. However, these differences were not significant, suggesting BMI may not be a primary driver of TF; active or uncontrolled disease potentially outweighs BMI’s influence on time to TF. This null finding aligns with conflicting literature about BMI and anti-TNF TR. Analysis is limited by small sample size, low event rate, high loss to follow up and limited statistical power.

Figure: Characteristics of the biologic-naïve IBD cohort, stratified by treatment response/outcome

Figure: Kaplan-Meier survival curve with time to anti-TNF treatment failure from the IBD cohort, stratified by BMI categories

Disclosures:

William Larsen-Alemany indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Patricia Figueroa-Rodriguez indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Claudia Amaya-Ardila indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Esther Torres: AbbVie – Grant/Research Support. Genentech-Roche – Grant/Research Support. Prometheus Laboratories – Grant/Research Support. Sanofi – Grant/Research Support.

William Larsen-Alemany, BS1, Patricia Figueroa-Rodriguez, BS2, Claudia P.. Amaya-Ardila, 2, Esther A. Torres, MD3. P1046 - Does BMI Influence Anti-TNF Treatment Response in IBD? A Longitudinal Analysis in Puerto Rican Patients, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1UPR Medical Sciences Campus, Ponce Health Sciences University, Guaynabo, Puerto Rico; 2University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus, San Juan, Puerto Rico; 3University of Puerto Rico School of Medicone, San Juan, Puerto Rico

Introduction: Studies investigating the relationship between BMI and anti-TNF treatment response (TR) in patients with IBD have yielded conflicting results, with some proposing that higher BMIs are associated with treatment failure while others have reported that there is no association between BMI and TR. We aimed to evaluate the relationship between BMI categories and anti-TNF TR in patients from the UPR Registry of IBD.

Methods: A cohort of biologic-naïve patients from 2000-2020 was selected. Patients were followed up for 12-24 months using electronic health records to evaluate TR: treatment failure (TF), sustained response (SR), or loss to follow-up. Univariate analysis was performed to describe demographics and IBD-characteristics according to TR with reported p-values. A Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival analysis based on time to TF and hazard ratios (HR) with the underweight/normal group as reference was performed. Statistical significance is set at p < 0.05. The study is approved by MSC-IRB.

Results: 136 patients were included for TR analysis, 111 had CD and 25 UC. 79 were underweight/normal weight, 34 overweight and 23 obese. 25 were lost to follow-up, 41 had TF while 70 had SR. Significant differences between TF and SR were observed with age, type of IBD, surgical history, current steroid use and current ASA use (p< 0.05); marginal significance was seen with CD location (p=0.070). Concurrent ASA use (aHR 2.7, p = 0.018), EIM (aHR 1.4, p = 0.073), concurrent steroid use (aHR 2.5, p = 0.096), perianal disease (aHR 1.7, p = 0.331), ileal vs. ileocolonic (aHR 0.96, p = 0.112) were associated with a higher risk of TF. Regression analysis for TR yielded HR of 1.4679 (p=0.258) for overweight and 0.5918 (p=0.333) for obese compared to the normal/underweight group, showing no statistical significance between BMI and time to TF (p >0.05).

Discussion: No overall association between BMI and time to TF was found. The KM curve suggests a slightly higher risk of TF for the overweight group and a potential protective effect for the obese group compared to the underweight/normal group. However, these differences were not significant, suggesting BMI may not be a primary driver of TF; active or uncontrolled disease potentially outweighs BMI’s influence on time to TF. This null finding aligns with conflicting literature about BMI and anti-TNF TR. Analysis is limited by small sample size, low event rate, high loss to follow up and limited statistical power.

Figure: Characteristics of the biologic-naïve IBD cohort, stratified by treatment response/outcome

Figure: Kaplan-Meier survival curve with time to anti-TNF treatment failure from the IBD cohort, stratified by BMI categories

Disclosures:

William Larsen-Alemany indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Patricia Figueroa-Rodriguez indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Claudia Amaya-Ardila indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Esther Torres: AbbVie – Grant/Research Support. Genentech-Roche – Grant/Research Support. Prometheus Laboratories – Grant/Research Support. Sanofi – Grant/Research Support.

William Larsen-Alemany, BS1, Patricia Figueroa-Rodriguez, BS2, Claudia P.. Amaya-Ardila, 2, Esther A. Torres, MD3. P1046 - Does BMI Influence Anti-TNF Treatment Response in IBD? A Longitudinal Analysis in Puerto Rican Patients, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.