Monday Poster Session

Category: Liver

P4005 - A Rare Case of Bleeding Splenic Varices in a Patient With Newly Diagnosed Cirrhosis

Monday, October 27, 2025

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Sanjna Shelukar, MD

Thomas Jefferson University Hospital

Philadelphia, PA

Presenting Author(s)

Sanjna Shelukar, MD1, Amit Agarwal, MD1, Jonathan Gross, MD2, David Truscello, DO3, Dina Halegoua-DeMarzio, MD1

1Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA; 2University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL; 3Cooper University Health Care, Cape May Court House, NJ

Introduction: In patients with cirrhosis, esophageal or gastric varices develop due to portal hypertension. As compensation, spontaneous portosystemic shunts can form. Ectopic varices, which occur at non-traditional sites, are rare. Among them, splenic varices can form with collaterals such as a spontaneous splenorenal shunt (SSRS). We present a patient with newly diagnosed cirrhosis, acute anemia, and no overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding who was found to have a splenic varix with SSRS.

Case Description/

Methods: A 56-year-old female with significant alcohol use, hypertension, and hemorrhoids, but no prior liver disease, presented with one month of fatigue, jaundice, and abdominal distention. She was hypotensive (76/39) and anemic (Hb 5.9 mg/dL) with a MELD of 31. Exam revealed jaundice, spider angiomas, abdominal distention, and asterixis. Initial imaging showed newly diagnosed cirrhosis, large-volume ascites, normal spleen, and patent portal vein.

She initially stabilized with perfusion, but on hospital day 4, developed acute anemia (Hb 5.8 mg/dL rising only to 7.5 mg/dL after 3 units pRBC), hypotension, and altered mental status. She had a blood-streaked stool thought to be hemorrhoidal, but no overt GI bleeding.

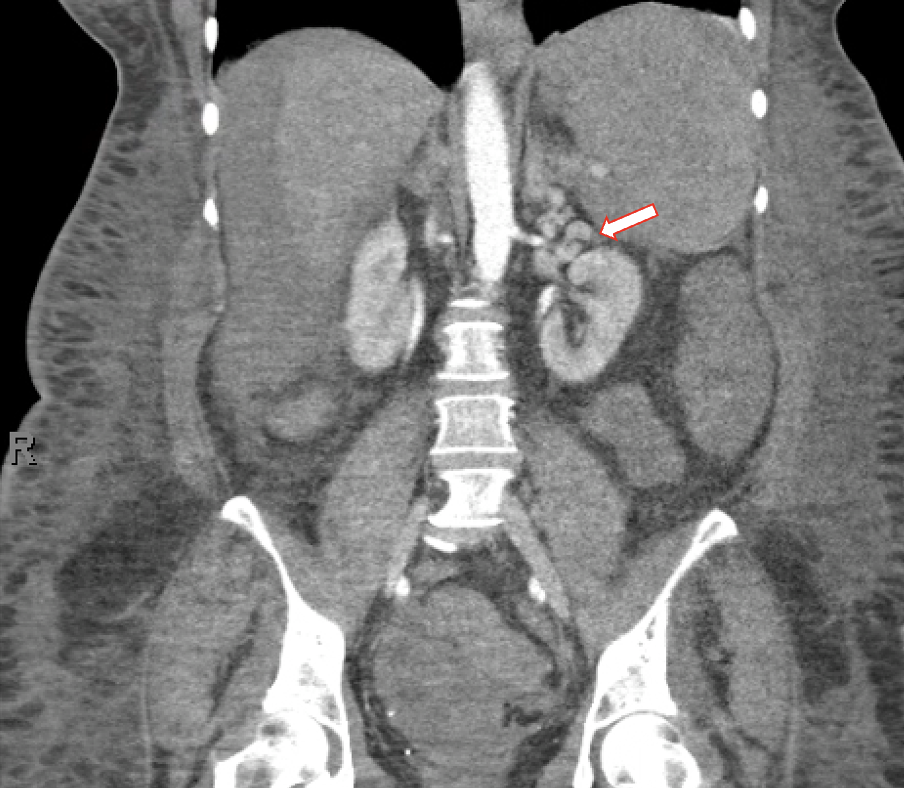

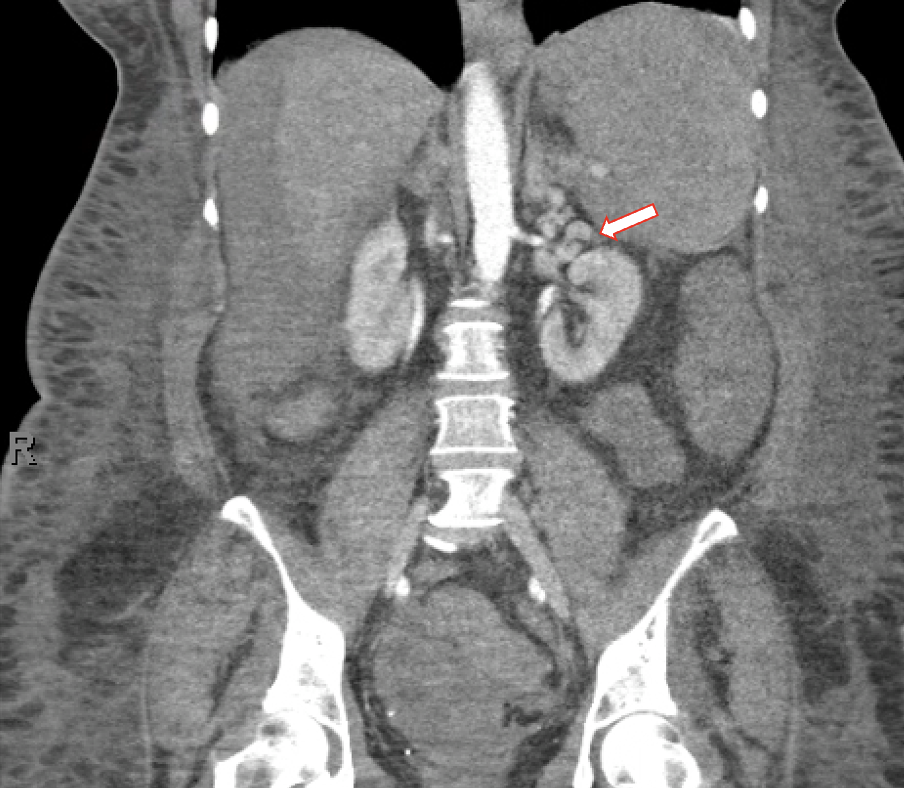

The patient’s rapid decompensation made her unsuitable for endoscopy and colonoscopy. We pursued CTA of the abdomen which revealed large perisplenic hematoma, splenic varices, splenorenal collateral, diffuse splenic infarction, and diffusely decreased liver perfusion (Figure 1). Octreotide was started for suspected variceal bleeding.

Given her rapid decline, infarcted spleen, high MELD, and poor hepatic perfusion, interventional treatment was infeasible. The family opted for comfort care, and the patient died shortly after.

Discussion: This case highlights the need to consider ectopic varices in cirrhotic patients with anemia and no overt GI bleeding. CTA was key in identifying the bleeding source.

Though rare, splenic varices are treated similarly to esophagogastric varices with octreotide for acute bleeding and beta-blockers for secondary prevention. Interventional options like transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO), and splenic embolization have been described but lack consensus guidelines. In this case, embolization was not viable due to splenic infarction and TIPS was high-risk due to liver malperfusion and high MELD.

Early consideration and imaging of ectopic varices are crucial for diagnosis and management.

Figure: Figure 1. Radiographic appearance of splenic varices, splenorenal shunt, and decreased perfusion to liver via abdominal CTA

Disclosures:

Sanjna Shelukar indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Amit Agarwal indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Jonathan Gross indicated no relevant financial relationships.

David Truscello indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Dina Halegoua-DeMarzio: 89BIO – Grant/Research Support. Akero – Grant/Research Support. Galectin – Grant/Research Support. Madigral – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Grant/Research Support, Speakers Bureau. Novo Nordisk – Grant/Research Support. Vertex – Advisor or Review Panel Member.

Sanjna Shelukar, MD1, Amit Agarwal, MD1, Jonathan Gross, MD2, David Truscello, DO3, Dina Halegoua-DeMarzio, MD1. P4005 - A Rare Case of Bleeding Splenic Varices in a Patient With Newly Diagnosed Cirrhosis, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA; 2University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL; 3Cooper University Health Care, Cape May Court House, NJ

Introduction: In patients with cirrhosis, esophageal or gastric varices develop due to portal hypertension. As compensation, spontaneous portosystemic shunts can form. Ectopic varices, which occur at non-traditional sites, are rare. Among them, splenic varices can form with collaterals such as a spontaneous splenorenal shunt (SSRS). We present a patient with newly diagnosed cirrhosis, acute anemia, and no overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding who was found to have a splenic varix with SSRS.

Case Description/

Methods: A 56-year-old female with significant alcohol use, hypertension, and hemorrhoids, but no prior liver disease, presented with one month of fatigue, jaundice, and abdominal distention. She was hypotensive (76/39) and anemic (Hb 5.9 mg/dL) with a MELD of 31. Exam revealed jaundice, spider angiomas, abdominal distention, and asterixis. Initial imaging showed newly diagnosed cirrhosis, large-volume ascites, normal spleen, and patent portal vein.

She initially stabilized with perfusion, but on hospital day 4, developed acute anemia (Hb 5.8 mg/dL rising only to 7.5 mg/dL after 3 units pRBC), hypotension, and altered mental status. She had a blood-streaked stool thought to be hemorrhoidal, but no overt GI bleeding.

The patient’s rapid decompensation made her unsuitable for endoscopy and colonoscopy. We pursued CTA of the abdomen which revealed large perisplenic hematoma, splenic varices, splenorenal collateral, diffuse splenic infarction, and diffusely decreased liver perfusion (Figure 1). Octreotide was started for suspected variceal bleeding.

Given her rapid decline, infarcted spleen, high MELD, and poor hepatic perfusion, interventional treatment was infeasible. The family opted for comfort care, and the patient died shortly after.

Discussion: This case highlights the need to consider ectopic varices in cirrhotic patients with anemia and no overt GI bleeding. CTA was key in identifying the bleeding source.

Though rare, splenic varices are treated similarly to esophagogastric varices with octreotide for acute bleeding and beta-blockers for secondary prevention. Interventional options like transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO), and splenic embolization have been described but lack consensus guidelines. In this case, embolization was not viable due to splenic infarction and TIPS was high-risk due to liver malperfusion and high MELD.

Early consideration and imaging of ectopic varices are crucial for diagnosis and management.

Figure: Figure 1. Radiographic appearance of splenic varices, splenorenal shunt, and decreased perfusion to liver via abdominal CTA

Disclosures:

Sanjna Shelukar indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Amit Agarwal indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Jonathan Gross indicated no relevant financial relationships.

David Truscello indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Dina Halegoua-DeMarzio: 89BIO – Grant/Research Support. Akero – Grant/Research Support. Galectin – Grant/Research Support. Madigral – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Grant/Research Support, Speakers Bureau. Novo Nordisk – Grant/Research Support. Vertex – Advisor or Review Panel Member.

Sanjna Shelukar, MD1, Amit Agarwal, MD1, Jonathan Gross, MD2, David Truscello, DO3, Dina Halegoua-DeMarzio, MD1. P4005 - A Rare Case of Bleeding Splenic Varices in a Patient With Newly Diagnosed Cirrhosis, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.