Tuesday Poster Session

Category: IBD

P5480 - Impact of Positive Family History on Outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Tuesday, October 28, 2025

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Bader Aldahash (he/him/his)

King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre

Riyadh, Ar Riyad, Saudi Arabia

Presenting Author(s)

Bader Aldahash, 1, Badr Al Bawardy, MD2, Alanoud Alshareef, 1, Mariam Elsayed, 1, Sameer Desai, 1, Abdulelah Almutairdi, MD1, Mashary Attamimi, MD1

1King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Riyadh, Ar Riyad, Saudi Arabia; 2Yale New Haven Hospital, New Haven, USA; King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, New Haven, CT

Introduction: While family history is known to increase inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) susceptibility, its influence on the disease's severity, complications, and treatment outcomes remains partially explored. This study aims to investigate the association between positive family history and IBD phenotypes and severity.

Methods: This was cross-sectional study of a prospectively maintained longitudinal database of IBD patients from Sep 1st, 2023-Sep 30th, 2024 in a tertiary healthcare center in Saudi Arabia. The study included all patients aged 14-years and older who had a confirmed diagnosis of IBD including Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), IBD-unclassified (IBD-U). Positive family history of IBD was defined as at least one either 1st or 2nd/3rd degree family member with IBD. The primary outcomes were prevalence of IBD family history and its association with IBD phenotypes. Secondary outcomes included the association of family history with intestinal surgeries, need for > 2 advanced therapies and composite outcome (intestinal surgery, > 2 advanced therapies).

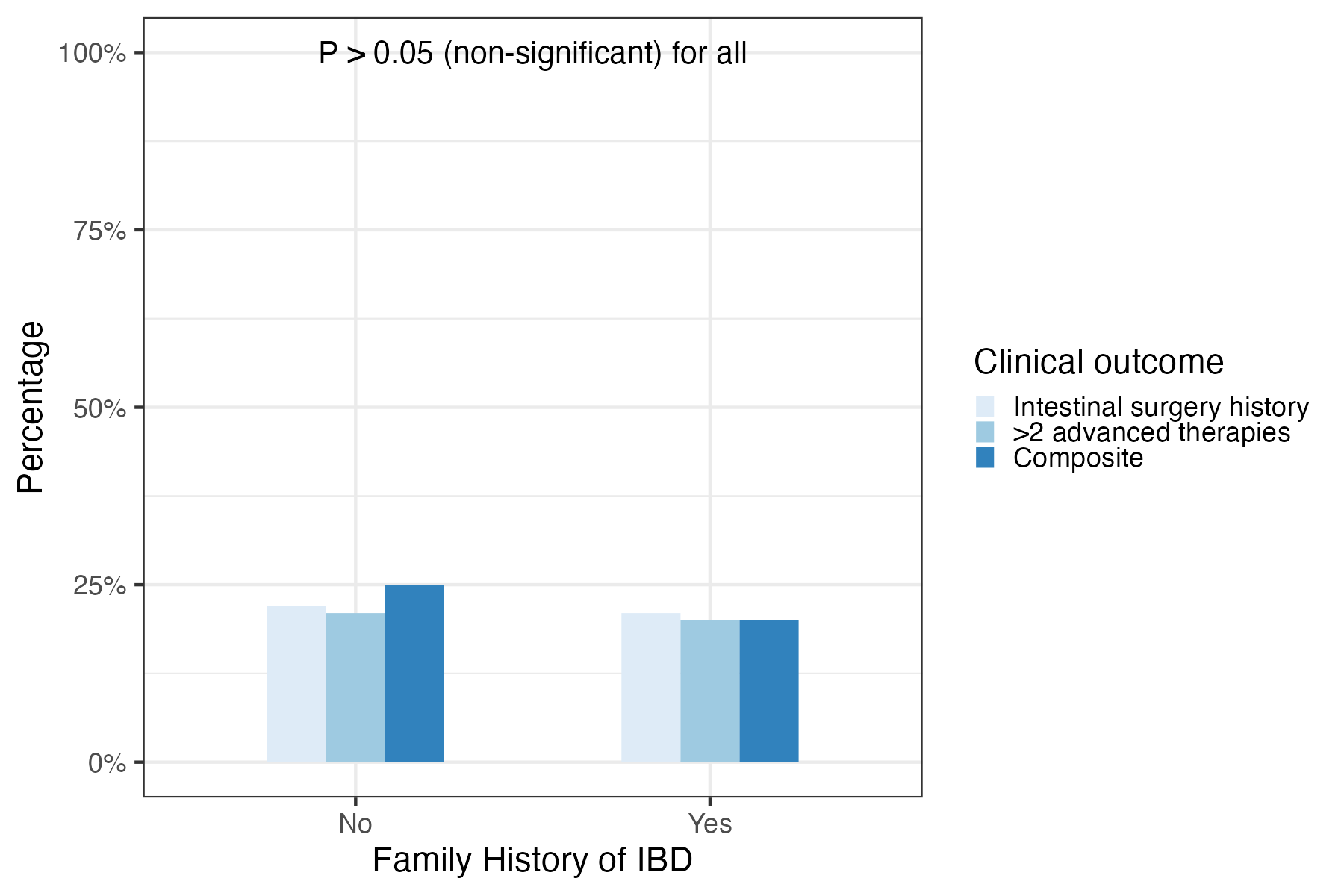

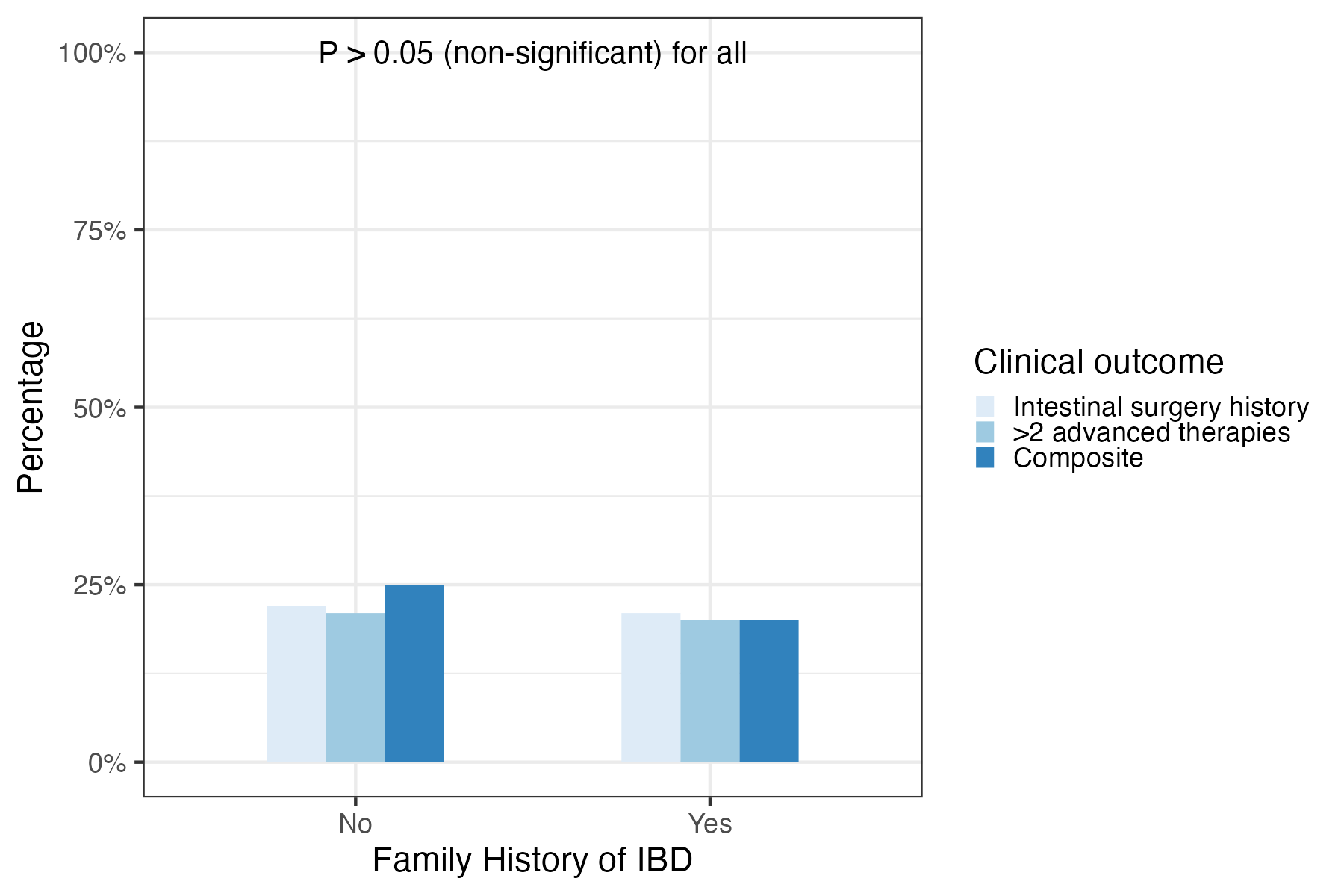

Results: A total of 412 patients were enrolled in the study (mean age 33 ± 13 years; 68% with CD, and 55% were male. A total of 22% (n=89) self-reported a family history of IBD (14% 1st degree and 7.3% 2nd/3rd degree relative). There was no significant association between IBD family history and stricturing phenotype (27% vs. 34%, p=0.4), penetrating phenotype (44% vs. 53%, p=0.4) and perianal disease (37% vs. 43%, p=0.4). The prevalence of pancolitis was similar in those with and without family history of IBD (42% vs. 56%, p=0.2). There were no significant differences in rates of intestinal surgery (p=0.9), need for > 2 advanced therapies (p=0.8), and composite outcome (p=0.2) between those with and without family history of IBD (Figure 1)

Discussion: The prevalence of family history of IBD in our cohort was high and could be reflective of referral bias. Family history of IBD was not associated with disease phenotypes or poor clinical outcomes. Larger studies are needed to evaluate the impact of family history of IBD on disease outcomes.

Figure: Comparison of intestinal surgery, need for more than two advanced therapies, and composite outcome.

Disclosures:

Bader Aldahash indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Badr Al Bawardy: AbbVie – Advisor or Review Panel Member, Consultant, Speakers Bureau. Bristol Myers Squibb – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Eli Lilly – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Hikma – Speakers Bureau. Janssen – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Pfizer – Advisory Committee/Board Member. TAKEDA – Advisor or Review Panel Member, Speakers Bureau.

Alanoud Alshareef indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Mariam Elsayed indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sameer Desai indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Abdulelah Almutairdi: AbbVie – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Amgen – Advisory Committee/Board Member. Bristol myers squibb – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Janssen – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Lilly – Advisory Committee/Board Member. Pfizer – Advisory Committee/Board Member. Takeda – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau.

Mashary Attamimi: AbbVie – Speakers Bureau. Hikma – Speakers Bureau. Janssen – Speakers Bureau. Lilly – Speakers Bureau. Pfizer – Speakers Bureau. Sandoz – Speakers Bureau. Takeda – Speakers Bureau.

Bader Aldahash, 1, Badr Al Bawardy, MD2, Alanoud Alshareef, 1, Mariam Elsayed, 1, Sameer Desai, 1, Abdulelah Almutairdi, MD1, Mashary Attamimi, MD1. P5480 - Impact of Positive Family History on Outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Riyadh, Ar Riyad, Saudi Arabia; 2Yale New Haven Hospital, New Haven, USA; King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, New Haven, CT

Introduction: While family history is known to increase inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) susceptibility, its influence on the disease's severity, complications, and treatment outcomes remains partially explored. This study aims to investigate the association between positive family history and IBD phenotypes and severity.

Methods: This was cross-sectional study of a prospectively maintained longitudinal database of IBD patients from Sep 1st, 2023-Sep 30th, 2024 in a tertiary healthcare center in Saudi Arabia. The study included all patients aged 14-years and older who had a confirmed diagnosis of IBD including Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), IBD-unclassified (IBD-U). Positive family history of IBD was defined as at least one either 1st or 2nd/3rd degree family member with IBD. The primary outcomes were prevalence of IBD family history and its association with IBD phenotypes. Secondary outcomes included the association of family history with intestinal surgeries, need for > 2 advanced therapies and composite outcome (intestinal surgery, > 2 advanced therapies).

Results: A total of 412 patients were enrolled in the study (mean age 33 ± 13 years; 68% with CD, and 55% were male. A total of 22% (n=89) self-reported a family history of IBD (14% 1st degree and 7.3% 2nd/3rd degree relative). There was no significant association between IBD family history and stricturing phenotype (27% vs. 34%, p=0.4), penetrating phenotype (44% vs. 53%, p=0.4) and perianal disease (37% vs. 43%, p=0.4). The prevalence of pancolitis was similar in those with and without family history of IBD (42% vs. 56%, p=0.2). There were no significant differences in rates of intestinal surgery (p=0.9), need for > 2 advanced therapies (p=0.8), and composite outcome (p=0.2) between those with and without family history of IBD (Figure 1)

Discussion: The prevalence of family history of IBD in our cohort was high and could be reflective of referral bias. Family history of IBD was not associated with disease phenotypes or poor clinical outcomes. Larger studies are needed to evaluate the impact of family history of IBD on disease outcomes.

Figure: Comparison of intestinal surgery, need for more than two advanced therapies, and composite outcome.

Disclosures:

Bader Aldahash indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Badr Al Bawardy: AbbVie – Advisor or Review Panel Member, Consultant, Speakers Bureau. Bristol Myers Squibb – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Eli Lilly – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Hikma – Speakers Bureau. Janssen – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Pfizer – Advisory Committee/Board Member. TAKEDA – Advisor or Review Panel Member, Speakers Bureau.

Alanoud Alshareef indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Mariam Elsayed indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sameer Desai indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Abdulelah Almutairdi: AbbVie – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Amgen – Advisory Committee/Board Member. Bristol myers squibb – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Janssen – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau. Lilly – Advisory Committee/Board Member. Pfizer – Advisory Committee/Board Member. Takeda – Advisory Committee/Board Member, Speakers Bureau.

Mashary Attamimi: AbbVie – Speakers Bureau. Hikma – Speakers Bureau. Janssen – Speakers Bureau. Lilly – Speakers Bureau. Pfizer – Speakers Bureau. Sandoz – Speakers Bureau. Takeda – Speakers Bureau.

Bader Aldahash, 1, Badr Al Bawardy, MD2, Alanoud Alshareef, 1, Mariam Elsayed, 1, Sameer Desai, 1, Abdulelah Almutairdi, MD1, Mashary Attamimi, MD1. P5480 - Impact of Positive Family History on Outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.