Tuesday Poster Session

Category: General Endoscopy

P5150 - The Pale Warning: White Nipple Sign on a Gastric Varix in a Patient With Hemorrhagic Shock

Tuesday, October 28, 2025

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

.jpg)

Akash Patel, MD (he/him/his)

University of Texas Southwestern

Dallas, TX

Presenting Author(s)

Akash Patel, MD, Antonio P. Machado, MD, Rozina Mithani, MD

University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX

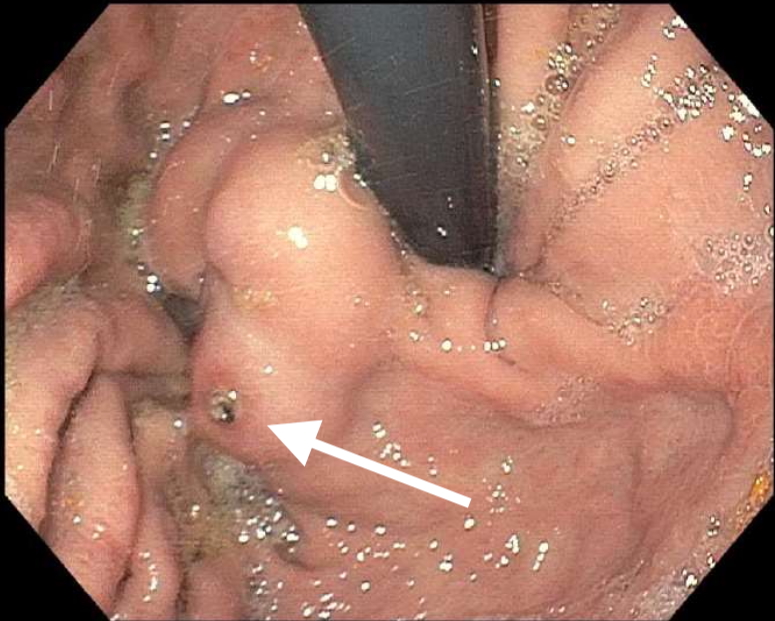

Introduction: Gastric varices are a less common source of bleeding among patients with cirrhosis. Like esophageal variceal bleeds, gastric variceal bleeding typically subsides by the time of endoscopic evaluation. In this case, familiarity with the stigmata of recent bleeding can help determine gastric varices as the source of bleeding. Here, we present an image of the “white nipple sign” on an isolated gastric varix type 1 (IGV1) identified as the source of hemorrhagic shock in a patient with chronic liver disease.

Case Description/

Methods: A 45-year-old female actively listed on the liver transplant list with a history of decompensated alcohol-associated cirrhosis presented with coffee-ground emesis, hematochezia, and fatigue. En route, her blood pressure was found to be 60/50 mmHg which improved with resuscitation with normal saline and packed red blood cells (pRBCs). On arrival, her lab work was notable for lactate of 3.3 mmol/L (ref range 0.5-2.2 mmol/L), BUN of 42 mg/dL (ref range 6-23), creatinine of 1.26 mg/dL (ref range 0.5-1.11), hemoglobin of 6.9 g/dL from a baseline of 9-10 g/dL (ref range 12-15), INR of 1.5, and otherwise normal liver enzymes. She was started on octreotide, proton pump inhibitor, and broad-spectrum antibiotics, and received an additional unit of pRBCs. She was taken to urgent endoscopy which demonstrated two non-bleeding grade 1 esophageal varices without stigmata and an IGV1 with a protuberant white spot (Figure 1) within the gastric fundus. Given the anatomic location of the varix and her transplant status, endoscopic therapies were deferred in favor of balloon retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement (TIPS) as a possible bridge to liver transplantation. She tolerated these procedures well and was able to be discharged with close follow-up.

Discussion: The “white nipple sign” was first described by Chung and Lewis in 1984. Manipulation of this finding can lead to dislodgement and “jet-like bleeding” or the “Mount St. Helens” sign. Recent studies have found its incidence to range between 5-24.3% of endoscopies for variceal bleeds. More commonly seen in the context of esophageal variceal bleeding, this case represents a rare image of the “white nipple sign” on an IGV1 lesion, identified as the cause of our patient’s hemorrhagic shock. Prompt identification of this lesion can reduce the risk of rebleeding during endoscopic evaluations.

Figure: “White Nipple” sign on gastric varices within the gastric fundus

Disclosures:

Akash Patel indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Antonio Machado indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Rozina Mithani indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Akash Patel, MD, Antonio P. Machado, MD, Rozina Mithani, MD. P5150 - The Pale Warning: White Nipple Sign on a Gastric Varix in a Patient With Hemorrhagic Shock, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX

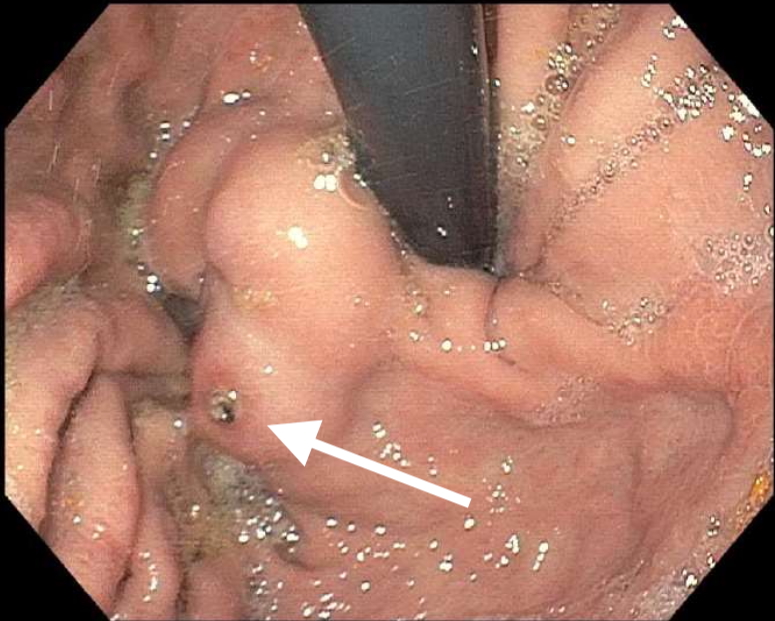

Introduction: Gastric varices are a less common source of bleeding among patients with cirrhosis. Like esophageal variceal bleeds, gastric variceal bleeding typically subsides by the time of endoscopic evaluation. In this case, familiarity with the stigmata of recent bleeding can help determine gastric varices as the source of bleeding. Here, we present an image of the “white nipple sign” on an isolated gastric varix type 1 (IGV1) identified as the source of hemorrhagic shock in a patient with chronic liver disease.

Case Description/

Methods: A 45-year-old female actively listed on the liver transplant list with a history of decompensated alcohol-associated cirrhosis presented with coffee-ground emesis, hematochezia, and fatigue. En route, her blood pressure was found to be 60/50 mmHg which improved with resuscitation with normal saline and packed red blood cells (pRBCs). On arrival, her lab work was notable for lactate of 3.3 mmol/L (ref range 0.5-2.2 mmol/L), BUN of 42 mg/dL (ref range 6-23), creatinine of 1.26 mg/dL (ref range 0.5-1.11), hemoglobin of 6.9 g/dL from a baseline of 9-10 g/dL (ref range 12-15), INR of 1.5, and otherwise normal liver enzymes. She was started on octreotide, proton pump inhibitor, and broad-spectrum antibiotics, and received an additional unit of pRBCs. She was taken to urgent endoscopy which demonstrated two non-bleeding grade 1 esophageal varices without stigmata and an IGV1 with a protuberant white spot (Figure 1) within the gastric fundus. Given the anatomic location of the varix and her transplant status, endoscopic therapies were deferred in favor of balloon retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement (TIPS) as a possible bridge to liver transplantation. She tolerated these procedures well and was able to be discharged with close follow-up.

Discussion: The “white nipple sign” was first described by Chung and Lewis in 1984. Manipulation of this finding can lead to dislodgement and “jet-like bleeding” or the “Mount St. Helens” sign. Recent studies have found its incidence to range between 5-24.3% of endoscopies for variceal bleeds. More commonly seen in the context of esophageal variceal bleeding, this case represents a rare image of the “white nipple sign” on an IGV1 lesion, identified as the cause of our patient’s hemorrhagic shock. Prompt identification of this lesion can reduce the risk of rebleeding during endoscopic evaluations.

Figure: “White Nipple” sign on gastric varices within the gastric fundus

Disclosures:

Akash Patel indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Antonio Machado indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Rozina Mithani indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Akash Patel, MD, Antonio P. Machado, MD, Rozina Mithani, MD. P5150 - The Pale Warning: White Nipple Sign on a Gastric Varix in a Patient With Hemorrhagic Shock, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.