Tuesday Poster Session

Category: Stomach and Spleen

P6404 - Challenging the Emergency: Conservative Management of Gastric Pneumatosis and Hepatoportal Venous Gas

Tuesday, October 28, 2025

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Yordan A. Urrutia, MD

University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine

Tampa, FL

Presenting Author(s)

Yordan A. Urrutia, MD1, Melanie Cabezas, MD1, Gitanjali Vidyarthi, MD2

1University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, FL; 2James A. Haley Veterans' Hospital, Tampa, FL

Introduction: Gastric pneumatosis often represents a clinically significant condition with a mortality rate recorded of up to 55%, may occur from gas-producing bacteria, and requires aggressive medical treatment and surgical intervention.1,2,3,4 This serious sequalae of gastric pneumatosis is termed emphysematous gastritis (EG). Alternatively, a subset of patients are hemodynamically stable and may have an unremarkable clinical course, and their diagnosis is known as gastric emphysema (GE).2 Because gastric pneumatosis is often associated with high acuity, it is crucial to differentiate between EG and GE and guide management.5 Additionally, hepatoportal venous gas (HPVG) can be a sequalae of gastric pneumatosis and usually also represents a serious abdominal pathology; however, rare cases have been reported with a benign clinical course.6,7

Case Description/

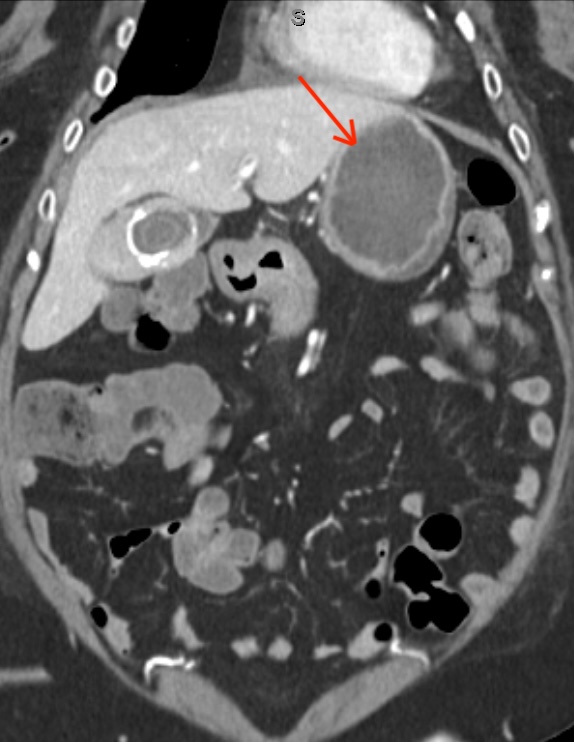

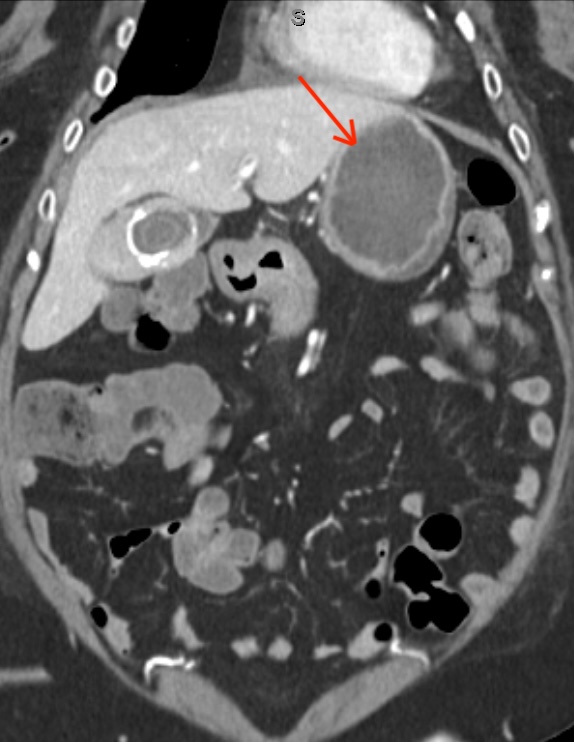

Methods: A 72-year-old-female with medical history significant for type 2 diabetes, GERD, and gastroparesis presented to the emergency department with 48 hours of worsening abdominal pain in the setting of one month of intractable nausea and vomiting. She was hemodynamically stable without tenderness, rebound, or guarding on exam. Labs significant for normal white blood cell count and lactate of 1.3. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed significant gastric wall thickening, extensive gastric pneumatosis, mild perigastric fat stranding, and HPVG (Figure 1). These findings were not present on CT a month prior and were concerning for emphysematous gastritis versus gastric emphysema. As the patient was stable with a benign physical exam, she was managed conservatively with antimicrobials, bowel rest, intravenous (IV) hydration, IV proton pump inhibitor, and daily abdominal x-rays which showed progressive improvement of gastric distention. Abdominal CT 4 days later revealed persistent gastric thickening with resolved gastric emphysema and nearly resolved HPVG (Figure 2).

Discussion: In this case, gastric emphysema and hepatoportal venous gas were caused by extensive emesis which likely led to injury to the gastric mucosa, air leak into the gastric wall, and spread to the portal venous system. The near complete resolution after conservative therapy supports that the findings were not due to a serious pathology. This case emphasizes the importance of correlating the findings of gastric pneumatosis to the clinical context and understanding that it could have a benign etiology to avoid harm with overly aggressive interventions.

Figure: Initial CT abdomen showing significant gastric wall thickening, extensive gastric pneumatosis associated with mesenteric and portal venous gas.

Figure: CT abdomen 4 days later showing persistent thickening of the stomach with resolved gastric emphysema and nearly resolved portal venous gas with some air in the left portal venous branches.

Disclosures:

Yordan Urrutia indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Melanie Cabezas indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Gitanjali Vidyarthi indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Yordan A. Urrutia, MD1, Melanie Cabezas, MD1, Gitanjali Vidyarthi, MD2. P6404 - Challenging the Emergency: Conservative Management of Gastric Pneumatosis and Hepatoportal Venous Gas, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, FL; 2James A. Haley Veterans' Hospital, Tampa, FL

Introduction: Gastric pneumatosis often represents a clinically significant condition with a mortality rate recorded of up to 55%, may occur from gas-producing bacteria, and requires aggressive medical treatment and surgical intervention.1,2,3,4 This serious sequalae of gastric pneumatosis is termed emphysematous gastritis (EG). Alternatively, a subset of patients are hemodynamically stable and may have an unremarkable clinical course, and their diagnosis is known as gastric emphysema (GE).2 Because gastric pneumatosis is often associated with high acuity, it is crucial to differentiate between EG and GE and guide management.5 Additionally, hepatoportal venous gas (HPVG) can be a sequalae of gastric pneumatosis and usually also represents a serious abdominal pathology; however, rare cases have been reported with a benign clinical course.6,7

Case Description/

Methods: A 72-year-old-female with medical history significant for type 2 diabetes, GERD, and gastroparesis presented to the emergency department with 48 hours of worsening abdominal pain in the setting of one month of intractable nausea and vomiting. She was hemodynamically stable without tenderness, rebound, or guarding on exam. Labs significant for normal white blood cell count and lactate of 1.3. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed significant gastric wall thickening, extensive gastric pneumatosis, mild perigastric fat stranding, and HPVG (Figure 1). These findings were not present on CT a month prior and were concerning for emphysematous gastritis versus gastric emphysema. As the patient was stable with a benign physical exam, she was managed conservatively with antimicrobials, bowel rest, intravenous (IV) hydration, IV proton pump inhibitor, and daily abdominal x-rays which showed progressive improvement of gastric distention. Abdominal CT 4 days later revealed persistent gastric thickening with resolved gastric emphysema and nearly resolved HPVG (Figure 2).

Discussion: In this case, gastric emphysema and hepatoportal venous gas were caused by extensive emesis which likely led to injury to the gastric mucosa, air leak into the gastric wall, and spread to the portal venous system. The near complete resolution after conservative therapy supports that the findings were not due to a serious pathology. This case emphasizes the importance of correlating the findings of gastric pneumatosis to the clinical context and understanding that it could have a benign etiology to avoid harm with overly aggressive interventions.

Figure: Initial CT abdomen showing significant gastric wall thickening, extensive gastric pneumatosis associated with mesenteric and portal venous gas.

Figure: CT abdomen 4 days later showing persistent thickening of the stomach with resolved gastric emphysema and nearly resolved portal venous gas with some air in the left portal venous branches.

Disclosures:

Yordan Urrutia indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Melanie Cabezas indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Gitanjali Vidyarthi indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Yordan A. Urrutia, MD1, Melanie Cabezas, MD1, Gitanjali Vidyarthi, MD2. P6404 - Challenging the Emergency: Conservative Management of Gastric Pneumatosis and Hepatoportal Venous Gas, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.