Monday Poster Session

Category: Interventional Endoscopy

P3602 - Recurrent Upper GI Bleeding Secondary to Gastroduodenal Arterial Embolization Microcoil Erosion at the Duodenal Bulb

Monday, October 27, 2025

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

David L. Hobby, MD (he/him/his)

Atrium Health Navicent

Atlanta, GA

Presenting Author(s)

David L. Hobby, MD, Roxana M. Coman, MD, PhD, Keely Small, PA-C, Elizabeth L. Lowery, PA, Davey R. Deal, MD

Atrium Health Navicent, Macon, GA

Introduction: Interventional Radiology directed arterial embolization has remained a pillar of treatment of refractory arterial gastrointestinal bleeding following endoscopic therapy. Radiologically placed coil migration and subsequent erosion through the gastrointestinal mucosa is an extremely rare complication following embolization.

Case Description/

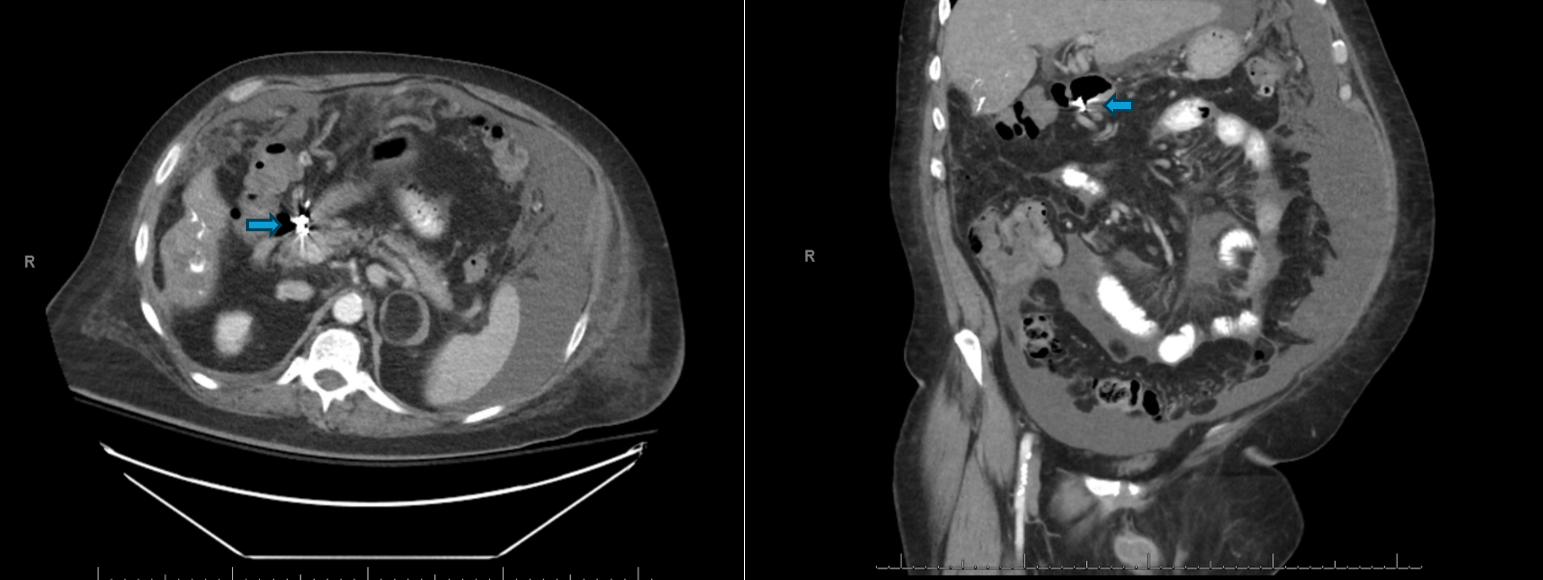

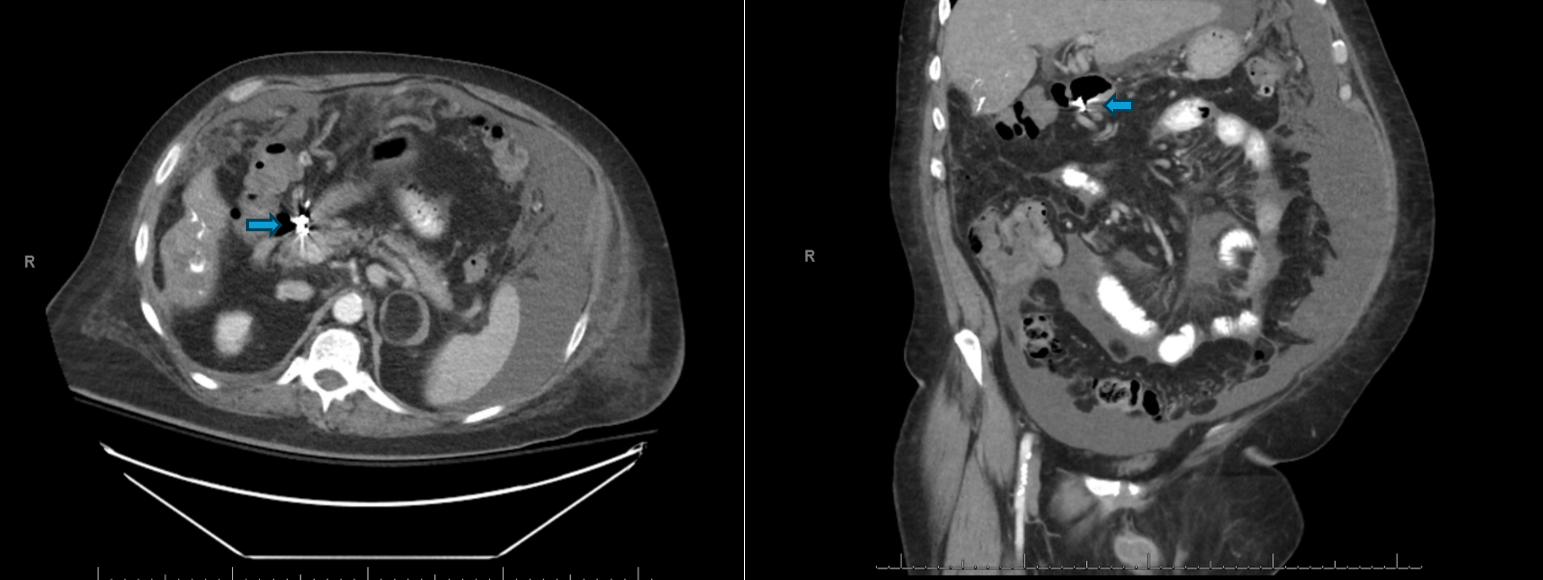

Methods: A 63-year-old male with a history of alcoholic cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and gastric varices presented to the Emergency Department with chief complaints of abdominal pain and melena. The patient had previously undergone an upper endoscopy 6 years prior for a bleeding duodenal ulcer unsuccessfully managed with electrocauterization and clip placement. The patient underwent IR-directed embolization at that time. On initial evaluation, the patient was found to be tachycardic (HR 120-130 bpm), hypotensive (BP 85/62 mmHg), and febrile (103oF). Physical exam noted large volume ascites and diffuse abdominal tenderness without guarding. CT abdomen/pelvis with contrast revealed abdominal ascites, numerous upper abdominal venous collaterals, peritoneal carcinomatosis, hypodensities within the inferior hepatic lobe, and a metallic structure near the proximal duodenum (Figure 1). White blood cell count was 43,000 uL with 33% Bands and a hemoglobin of 9.5 g/dL (baseline 13.3 g/dL). Paracentesis was then performed with fluid analysis containing a PMN count of 997 cells/mm3, consistent with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and Piperacillin/Tazobactam was initiated. The patient was started on IV Pantoprazole twice daily and IV Octreotide infusion. Upper endoscopy revealed an unexpected erosive metallic coil embedded in the mucosa of the duodenum (Fig. 2A). A large nonbleeding ulcer with adherent eschar was visualized adjacent to the protruding metallic coil (Fig. 2B). Gastric varices were identified without the stigmata of bleeding (Fig. 2C). The remaining hospital course was uncomplicated with SBP resolution. The patient was discharged in stable condition on Hospital Day 10 on antibiotic prophylaxis and a proton pump inhibitor.

Discussion: Microcoil erosion is believed to be due to a combination of a local inflammatory reaction and noncompliance with medical therapy. Coil erosion does not typically require intervention. However, treatment of unstable patients with persistent bleeding secondary to coil erosion can be emergent, and need for intervention should be reviewed on a case-by-case basis using a multi-disciplinary team.

Figure: Figure 1: Computed Tomography with oral contrast noting loculated abdominal ascites, hyperdense material with hypodensity in the inferior right hepatic lobe with underlying cirrhotic morphology in addition to a metallic structure at the duodenal bulb that appears to extend within the lumen (blue arrows).

Figure: Figure 2A: Metallic coil material embedded in the mucosa of the duodenal bulb projecting into the lumen, suggestive of previously placed gastroduodenal arterial coils. 2B: Adjacent duodenal bulb ulcer with adherent eschar without active bleeding. 2C: Chronic gastric varices noted without stigmata of recent bleeding in the absence of old or fresh blood in the stomach.

Disclosures:

David Hobby indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Roxana Coman indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Keely Small indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Elizabeth Lowery indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Davey Deal indicated no relevant financial relationships.

David L. Hobby, MD, Roxana M. Coman, MD, PhD, Keely Small, PA-C, Elizabeth L. Lowery, PA, Davey R. Deal, MD. P3602 - Recurrent Upper GI Bleeding Secondary to Gastroduodenal Arterial Embolization Microcoil Erosion at the Duodenal Bulb, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

Atrium Health Navicent, Macon, GA

Introduction: Interventional Radiology directed arterial embolization has remained a pillar of treatment of refractory arterial gastrointestinal bleeding following endoscopic therapy. Radiologically placed coil migration and subsequent erosion through the gastrointestinal mucosa is an extremely rare complication following embolization.

Case Description/

Methods: A 63-year-old male with a history of alcoholic cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and gastric varices presented to the Emergency Department with chief complaints of abdominal pain and melena. The patient had previously undergone an upper endoscopy 6 years prior for a bleeding duodenal ulcer unsuccessfully managed with electrocauterization and clip placement. The patient underwent IR-directed embolization at that time. On initial evaluation, the patient was found to be tachycardic (HR 120-130 bpm), hypotensive (BP 85/62 mmHg), and febrile (103oF). Physical exam noted large volume ascites and diffuse abdominal tenderness without guarding. CT abdomen/pelvis with contrast revealed abdominal ascites, numerous upper abdominal venous collaterals, peritoneal carcinomatosis, hypodensities within the inferior hepatic lobe, and a metallic structure near the proximal duodenum (Figure 1). White blood cell count was 43,000 uL with 33% Bands and a hemoglobin of 9.5 g/dL (baseline 13.3 g/dL). Paracentesis was then performed with fluid analysis containing a PMN count of 997 cells/mm3, consistent with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and Piperacillin/Tazobactam was initiated. The patient was started on IV Pantoprazole twice daily and IV Octreotide infusion. Upper endoscopy revealed an unexpected erosive metallic coil embedded in the mucosa of the duodenum (Fig. 2A). A large nonbleeding ulcer with adherent eschar was visualized adjacent to the protruding metallic coil (Fig. 2B). Gastric varices were identified without the stigmata of bleeding (Fig. 2C). The remaining hospital course was uncomplicated with SBP resolution. The patient was discharged in stable condition on Hospital Day 10 on antibiotic prophylaxis and a proton pump inhibitor.

Discussion: Microcoil erosion is believed to be due to a combination of a local inflammatory reaction and noncompliance with medical therapy. Coil erosion does not typically require intervention. However, treatment of unstable patients with persistent bleeding secondary to coil erosion can be emergent, and need for intervention should be reviewed on a case-by-case basis using a multi-disciplinary team.

Figure: Figure 1: Computed Tomography with oral contrast noting loculated abdominal ascites, hyperdense material with hypodensity in the inferior right hepatic lobe with underlying cirrhotic morphology in addition to a metallic structure at the duodenal bulb that appears to extend within the lumen (blue arrows).

Figure: Figure 2A: Metallic coil material embedded in the mucosa of the duodenal bulb projecting into the lumen, suggestive of previously placed gastroduodenal arterial coils. 2B: Adjacent duodenal bulb ulcer with adherent eschar without active bleeding. 2C: Chronic gastric varices noted without stigmata of recent bleeding in the absence of old or fresh blood in the stomach.

Disclosures:

David Hobby indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Roxana Coman indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Keely Small indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Elizabeth Lowery indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Davey Deal indicated no relevant financial relationships.

David L. Hobby, MD, Roxana M. Coman, MD, PhD, Keely Small, PA-C, Elizabeth L. Lowery, PA, Davey R. Deal, MD. P3602 - Recurrent Upper GI Bleeding Secondary to Gastroduodenal Arterial Embolization Microcoil Erosion at the Duodenal Bulb, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.