Sunday Poster Session

Category: GI Bleeding

P0989 - Cecal Dieulafoy’s Lesion: A Rare Cause of Recurrent GI Bleeding

Sunday, October 26, 2025

3:30 PM - 7:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

- KT

Kathryn Thompson, MD

Emory University School of Medicine

Atlanta, GA

Presenting Author(s)

Kathryn Thompson, MD, Nicholas Austin, MD

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA

Introduction: Dieulafoy’s lesions are rare causes of acute GI bleeds and less than 5% of cases occur in the cecum. Dieulafoy’s lesions can be easily overlooked during endoscopy due to their small size and lack of ulceration and there are no known risk factors for developing them making the diagnosis challenging.

Case Description/

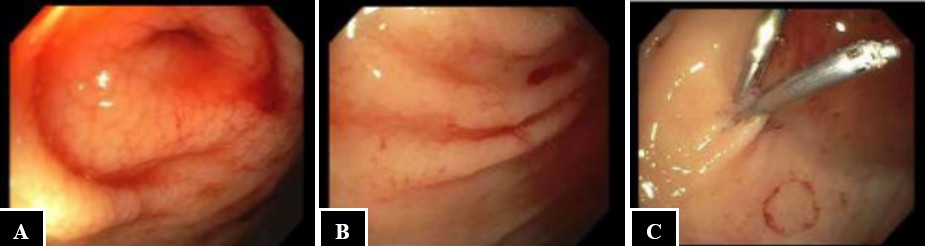

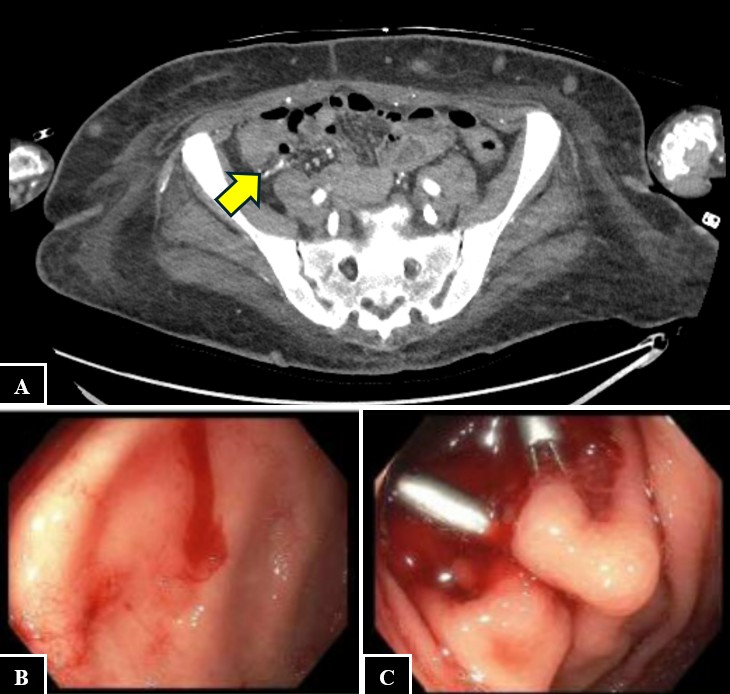

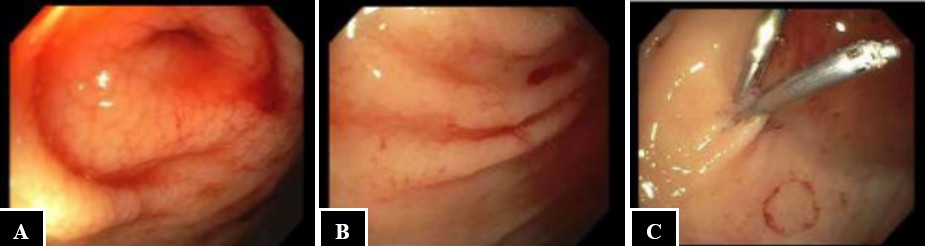

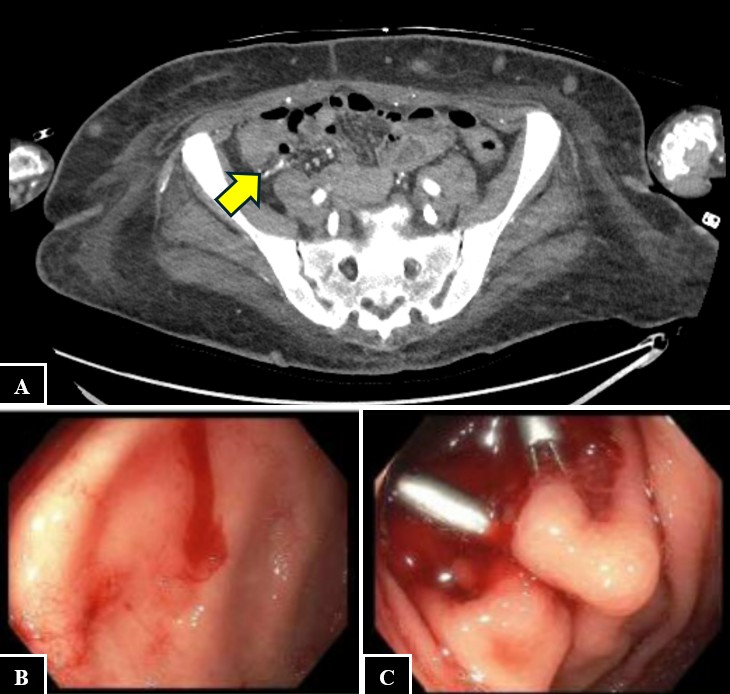

Methods: A 63-year-old female with a history of end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis presented with acute on chronic anemia in the setting of two-day history of melena. Her hemoglobin was 5.3 g/dL on admission which responded to transfusion support. She underwent colonoscopy which showed a cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion with active bleeding requiring placement of two hemostatic clips, and she was discharged shortly thereafter (Figure 1). Nine months later, she developed hematochezia during a prolonged hospital course, and her hemoglobin gradually declined to 7-9 g/dL from a baseline of 9-11 g/dL. CT angiography (CTA) of the abdomen demonstrated thin linear arterial enhancement with portal venous pooling at the cecum suggestive of a slow GI bleed at the site of prior cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion (Figure 2A). Interventional Radiology performed angiography of the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries and right colic artery but found no evidence of active bleed. She then underwent colonoscopy which showed recurrence of a cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion with active bleeding requiring placement of two hemostatic clips (Figure 2B-C). She had no further bleeding and hemoglobin remained stable after intervention.

Discussion: Dieulafoy’s lesions are commonly found along the lesser curvature of the stomach near the gastroesophageal junction, and only a small number of cases in the cecum are reported in the literature. They typically present as an acute GI bleed and can be severe enough to cause hemodynamic instability. This patient presented with melena during her initial presentation and then with acute-onset hematochezia when it recurred. CTA of the abdomen can help identify Dieulafoy’s lesions especially when endoscopic techniques are non-diagnostic and, in this case, it helped identify the source of bleed when it recurred prior to colonoscopy. Treatment options for Dieulafoy’s lesions include argon plasma coagulation, thermocoagulation, electrocoagulation, submucosal injection of epinephrine, and hemostatic clips. This case highlights a rare recurrence of cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion and though uncommon, one should consider Dieulafoy’s lesion as a possible etiology for lower GI bleeds.

Figure: Figure 1. Views of the cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion (A-C) with placement of two hemostatic clips (C) during the patient’s first admission.

Figure: Figure 2. CTA GI bleed showing thin linear arterial enhancement with portal venous pooling at the cecum suggestive of small slow GI bleed at the site of prior cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion (A). Views of the cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion (B-C) with placement of two hemostatic clips (C) during the patient’s second admission.

Disclosures:

Kathryn Thompson indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Nicholas Austin indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Kathryn Thompson, MD, Nicholas Austin, MD. P0989 - Cecal Dieulafoy’s Lesion: A Rare Cause of Recurrent GI Bleeding, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA

Introduction: Dieulafoy’s lesions are rare causes of acute GI bleeds and less than 5% of cases occur in the cecum. Dieulafoy’s lesions can be easily overlooked during endoscopy due to their small size and lack of ulceration and there are no known risk factors for developing them making the diagnosis challenging.

Case Description/

Methods: A 63-year-old female with a history of end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis presented with acute on chronic anemia in the setting of two-day history of melena. Her hemoglobin was 5.3 g/dL on admission which responded to transfusion support. She underwent colonoscopy which showed a cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion with active bleeding requiring placement of two hemostatic clips, and she was discharged shortly thereafter (Figure 1). Nine months later, she developed hematochezia during a prolonged hospital course, and her hemoglobin gradually declined to 7-9 g/dL from a baseline of 9-11 g/dL. CT angiography (CTA) of the abdomen demonstrated thin linear arterial enhancement with portal venous pooling at the cecum suggestive of a slow GI bleed at the site of prior cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion (Figure 2A). Interventional Radiology performed angiography of the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries and right colic artery but found no evidence of active bleed. She then underwent colonoscopy which showed recurrence of a cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion with active bleeding requiring placement of two hemostatic clips (Figure 2B-C). She had no further bleeding and hemoglobin remained stable after intervention.

Discussion: Dieulafoy’s lesions are commonly found along the lesser curvature of the stomach near the gastroesophageal junction, and only a small number of cases in the cecum are reported in the literature. They typically present as an acute GI bleed and can be severe enough to cause hemodynamic instability. This patient presented with melena during her initial presentation and then with acute-onset hematochezia when it recurred. CTA of the abdomen can help identify Dieulafoy’s lesions especially when endoscopic techniques are non-diagnostic and, in this case, it helped identify the source of bleed when it recurred prior to colonoscopy. Treatment options for Dieulafoy’s lesions include argon plasma coagulation, thermocoagulation, electrocoagulation, submucosal injection of epinephrine, and hemostatic clips. This case highlights a rare recurrence of cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion and though uncommon, one should consider Dieulafoy’s lesion as a possible etiology for lower GI bleeds.

Figure: Figure 1. Views of the cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion (A-C) with placement of two hemostatic clips (C) during the patient’s first admission.

Figure: Figure 2. CTA GI bleed showing thin linear arterial enhancement with portal venous pooling at the cecum suggestive of small slow GI bleed at the site of prior cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion (A). Views of the cecal Dieulafoy’s lesion (B-C) with placement of two hemostatic clips (C) during the patient’s second admission.

Disclosures:

Kathryn Thompson indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Nicholas Austin indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Kathryn Thompson, MD, Nicholas Austin, MD. P0989 - Cecal Dieulafoy’s Lesion: A Rare Cause of Recurrent GI Bleeding, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.