Sunday Poster Session

Category: GI Bleeding

P0956 - Pseudocirrhosis Unmasked: A Rare Case of Malignancy-Driven Esophageal Variceal Bleeding in a Non-Cirrhotic Patient

Sunday, October 26, 2025

3:30 PM - 7:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Saba Altarawneh, MD

Jersey City Medical Center

Jersey City, NJ

Presenting Author(s)

Award: ACG Presidential Poster Award

Saba Altarawneh, MD1, Cheryce Fraser, MD1, Amro Altarawneh, MD2, Etan Spira, MD1, Neal Carlin, MD1, Joseph DePasquale, MD1

1Jersey City Medical Center, Jersey City, NJ; 2Marshall University Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, Huntington, WV

Introduction: Esophageal variceal bleeding is typically linked to cirrhotic portal hypertension. However, rare non-cirrhotic causes can produce similar hemodynamic consequences. Pseudocirrhosis, a radiologic mimic of cirrhosis often caused by metastatic cancer, is an underrecognized etiology that may lead to life-threatening upper GI bleeding. We present a striking case of variceal hemorrhage in a non-cirrhotic patient, ultimately attributed to colorectal cancer metastases.

Case Description/

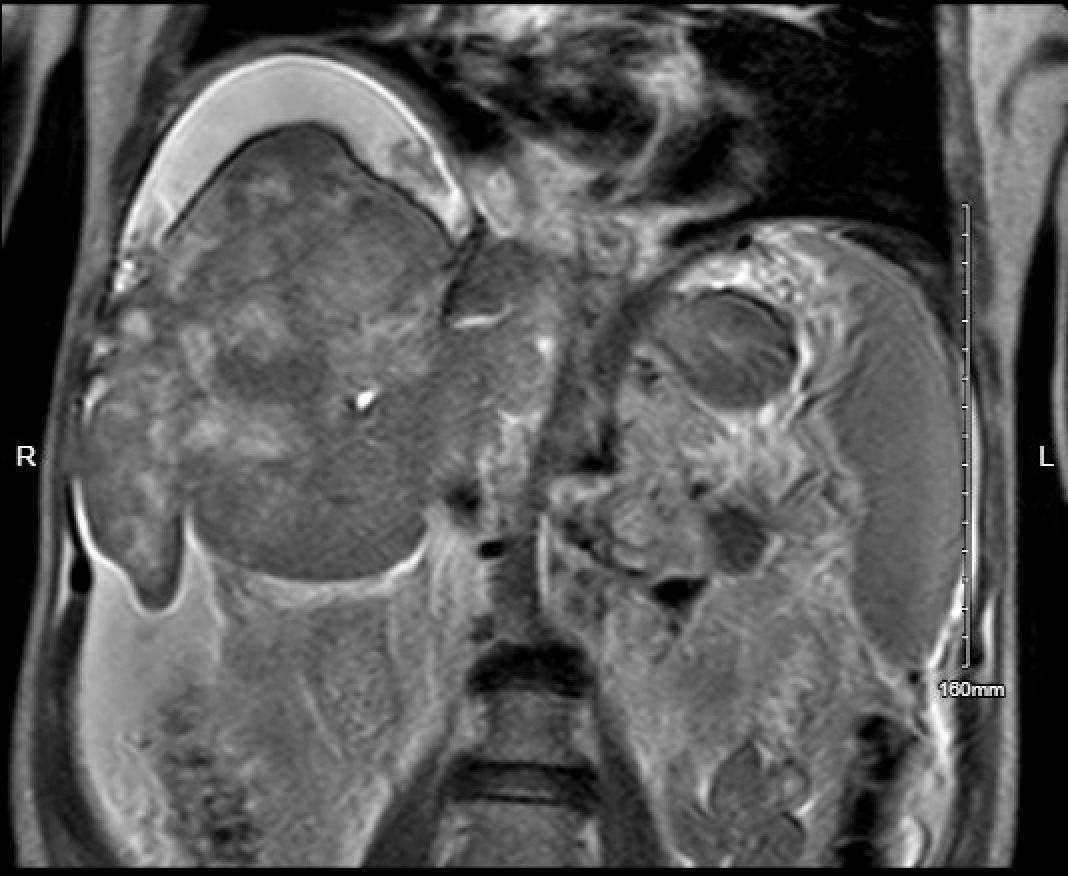

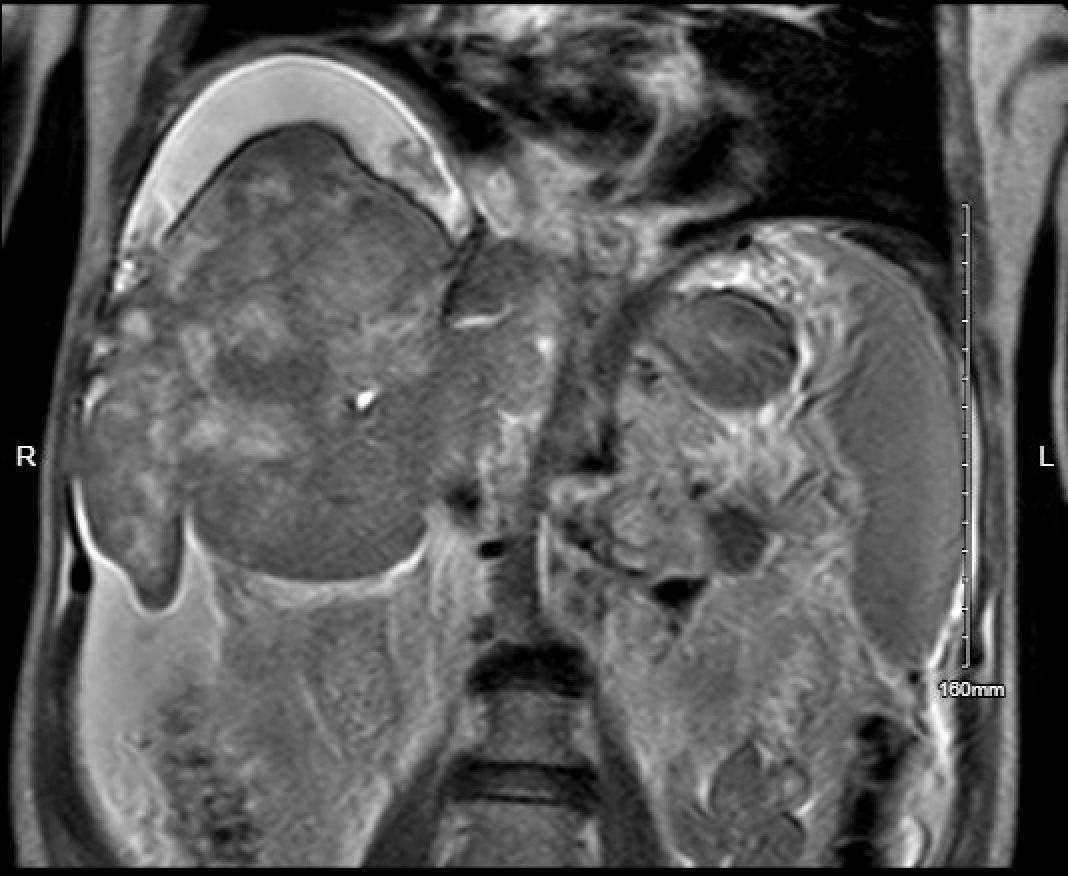

Methods: A 57-year-old male with a history of hepatitis C (now RNA-negative) and alcohol use disorder (abstinent for 11 months) presented with acute hematemesis and melena. He endorsed chronic NSAID use for back pain. On admission, he was tachycardic (HR 110–130s) with normocytic anemia (Hb 7.1), WBC 13.7, platelets 275, INR 1.37, and elevated liver enzymes (AST 211, ALT 87, ALP 543). Total bilirubin was 2.3, and albumin 2.8. He was started on octreotide, pantoprazole, and ceftriaxone for suspected variceal or ulcer bleeding. Emergent EGD revealed large esophageal varices with red wale signs, successfully managed with band ligation. Subsequent CT and MRI showed innumerable hepatic masses with the largest measuring 14.8 cm, trace ascites, mild intrahepatic biliary ductal dilation, and signs of pseudocirrhosis with possible portal vein thrombosis. Paracentesis was consistent with portal hypertension, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was ruled out. CEA was markedly elevated ( >2000), prompting colonoscopy, which revealed an obstructing sigmoid adenocarcinoma. A Port-A-Cath was placed for outpatient chemotherapy initiation.

Discussion: This case highlights an uncommon but critical cause of variceal bleeding: portal hypertensionsecondary to hepatic metastases,not cirrhosis. Pseudocirrhosis from tumor infiltration distorted liver architecture, likely obstructing portal flow and precipitating variceal formation. Although classically seen in breast cancer, pseudocirrhosis may arise from GI malignancies and mimic decompensated cirrhosis on imaging.

Clinicians should maintain a broad differential in patients with variceal bleeding but no classic cirrhotic history. Elevated tumor markers and early cross-sectional imaging can uncover an oncologic etiology. Prompt recognition enables both hemostatic intervention and timely cancer-directed care. This case reinforces the importance of recognizing malignancy-driven portalhypertension as a potential cause of variceal hemorrhage in non-cirrhotic patients.

Figure: CT scan axial view Pseudocirrhosis

Figure: MRI T2 Coronal View Pseudocirrhosis

Disclosures:

Saba Altarawneh indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Cheryce Fraser indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Amro Altarawneh indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Etan Spira indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Neal Carlin indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Joseph DePasquale indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Saba Altarawneh, MD1, Cheryce Fraser, MD1, Amro Altarawneh, MD2, Etan Spira, MD1, Neal Carlin, MD1, Joseph DePasquale, MD1. P0956 - Pseudocirrhosis Unmasked: A Rare Case of Malignancy-Driven Esophageal Variceal Bleeding in a Non-Cirrhotic Patient, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

Saba Altarawneh, MD1, Cheryce Fraser, MD1, Amro Altarawneh, MD2, Etan Spira, MD1, Neal Carlin, MD1, Joseph DePasquale, MD1

1Jersey City Medical Center, Jersey City, NJ; 2Marshall University Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, Huntington, WV

Introduction: Esophageal variceal bleeding is typically linked to cirrhotic portal hypertension. However, rare non-cirrhotic causes can produce similar hemodynamic consequences. Pseudocirrhosis, a radiologic mimic of cirrhosis often caused by metastatic cancer, is an underrecognized etiology that may lead to life-threatening upper GI bleeding. We present a striking case of variceal hemorrhage in a non-cirrhotic patient, ultimately attributed to colorectal cancer metastases.

Case Description/

Methods: A 57-year-old male with a history of hepatitis C (now RNA-negative) and alcohol use disorder (abstinent for 11 months) presented with acute hematemesis and melena. He endorsed chronic NSAID use for back pain. On admission, he was tachycardic (HR 110–130s) with normocytic anemia (Hb 7.1), WBC 13.7, platelets 275, INR 1.37, and elevated liver enzymes (AST 211, ALT 87, ALP 543). Total bilirubin was 2.3, and albumin 2.8. He was started on octreotide, pantoprazole, and ceftriaxone for suspected variceal or ulcer bleeding. Emergent EGD revealed large esophageal varices with red wale signs, successfully managed with band ligation. Subsequent CT and MRI showed innumerable hepatic masses with the largest measuring 14.8 cm, trace ascites, mild intrahepatic biliary ductal dilation, and signs of pseudocirrhosis with possible portal vein thrombosis. Paracentesis was consistent with portal hypertension, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was ruled out. CEA was markedly elevated ( >2000), prompting colonoscopy, which revealed an obstructing sigmoid adenocarcinoma. A Port-A-Cath was placed for outpatient chemotherapy initiation.

Discussion: This case highlights an uncommon but critical cause of variceal bleeding: portal hypertensionsecondary to hepatic metastases,not cirrhosis. Pseudocirrhosis from tumor infiltration distorted liver architecture, likely obstructing portal flow and precipitating variceal formation. Although classically seen in breast cancer, pseudocirrhosis may arise from GI malignancies and mimic decompensated cirrhosis on imaging.

Clinicians should maintain a broad differential in patients with variceal bleeding but no classic cirrhotic history. Elevated tumor markers and early cross-sectional imaging can uncover an oncologic etiology. Prompt recognition enables both hemostatic intervention and timely cancer-directed care. This case reinforces the importance of recognizing malignancy-driven portalhypertension as a potential cause of variceal hemorrhage in non-cirrhotic patients.

Figure: CT scan axial view Pseudocirrhosis

Figure: MRI T2 Coronal View Pseudocirrhosis

Disclosures:

Saba Altarawneh indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Cheryce Fraser indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Amro Altarawneh indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Etan Spira indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Neal Carlin indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Joseph DePasquale indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Saba Altarawneh, MD1, Cheryce Fraser, MD1, Amro Altarawneh, MD2, Etan Spira, MD1, Neal Carlin, MD1, Joseph DePasquale, MD1. P0956 - Pseudocirrhosis Unmasked: A Rare Case of Malignancy-Driven Esophageal Variceal Bleeding in a Non-Cirrhotic Patient, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.