Sunday Poster Session

Category: Esophagus

P0725 - Acute Esophageal Necrosis in a Critically Ill Patient: A Rare and Lethal Cause of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Sunday, October 26, 2025

3:30 PM - 7:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Bianca Thakkar, DO

University of Connecticut Health

Farmington, CT

Presenting Author(s)

Bianca Thakkar, DO1, Rachael Hagen, DO1, Courtney Stead, MD2, Maria Gorgan, MD3, Martin Hoffman, DO3

1University of Connecticut Health, Farmington, CT; 2University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT; 3Saint Francis Hospital, Trinity Health of New England, Hartford, CT

Introduction: Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), also known as “black esophagus,” is a rare, life-threatening condition characterized by diffuse circumferential black discoloration of the esophageal mucosa, typically affecting the distal esophagus with a sharp demarcation at the gastroesophageal junction. AEN is most often associated with a combination of ischemic insult, gastric acid reflux, and impaired mucosal defenses, typically in the context of systemic illness, hemodynamic instability, or multiorgan failure.

Case Description/

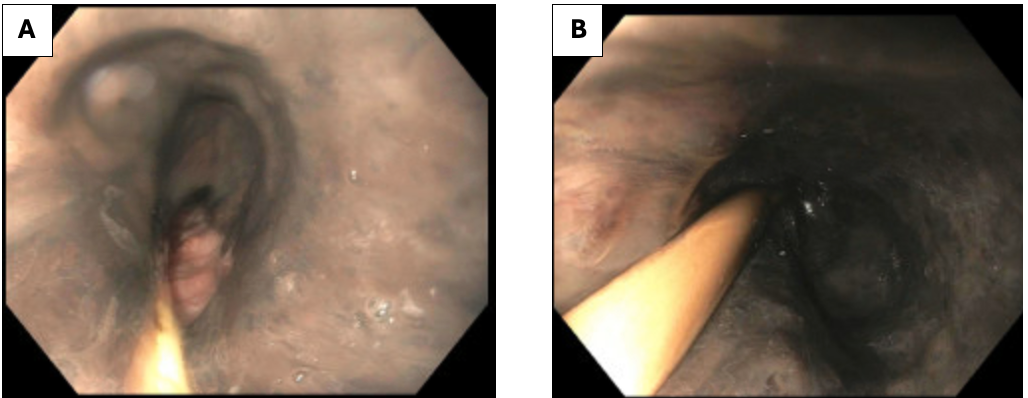

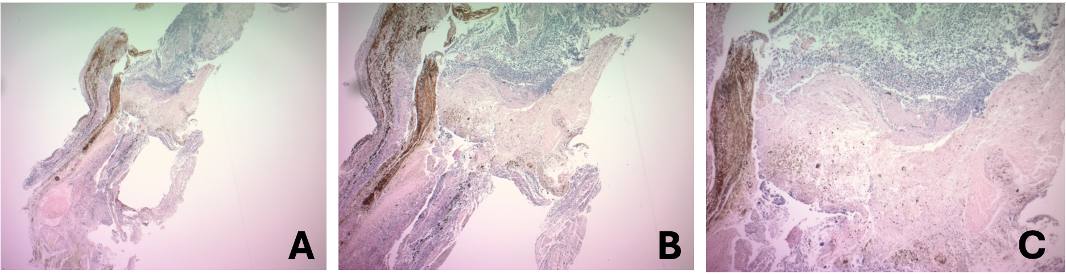

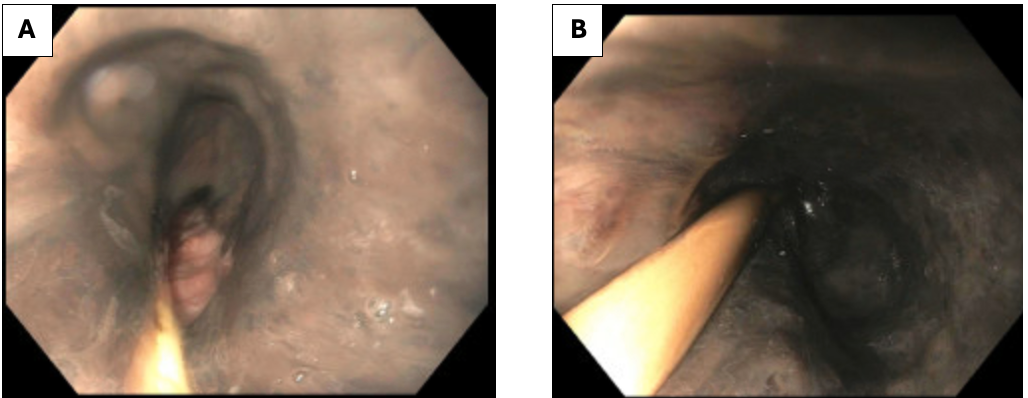

Methods: A 77-year-old female with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease presented with acute altered mental status, coffee-ground emesis, and signs of hemodynamic compromise. She was hypotensive, hypothermic, and in early septic shock, with labs notable for leukocytosis, anemia, elevated lactate (16 mmol/L), and acute kidney injury. Imaging revealed a cirrhotic-appearing liver with ascites and a large hiatal hernia with esophageal dilation. Her hospital course was complicated by hypoxic respiratory failure, worsening renal function, and melena requiring multiple transfusions and vasopressor support. She was empirically treated for variceal bleeding with an octreotide drip. Upper endoscopy revealed circumferential black discoloration of the esophagus consistent with AEN. Biopsies confirmed mucosal necrosis. Despite aggressive supportive care, her condition deteriorated, and after goals-of-care discussions, she was transitioned to comfort care and subsequently passed away.

Discussion: AEN remains a rare but critical diagnosis, often presenting with upper GI bleeding and occurring in elderly patients with significant comorbidities. The pathophysiology involves a synergistic combination of hypoperfusion, acid-mediated injury, and impaired mucosal repair. Diagnosis is confirmed via endoscopy and histopathology. Management is primarily supportive, emphasizing hemodynamic stabilization, PPI therapy, bowel rest, and addressing underlying causes. Mortality remains high, driven largely by the severity of associated systemic illness rather than the esophageal necrosis itself.

This case highlights the importance of considering AEN in critically ill patients presenting with GI bleeding and multiple comorbidities. Prompt recognition, supportive care, and early endoscopic evaluation are essential to guide management and prognostication.

Figure: Figure 1. Endoscopy (EGD) which shows upper third of the esophagus (A) and middle third of the esophagus (B), which appears grossly black, highly concerning for esophageal necrosis.

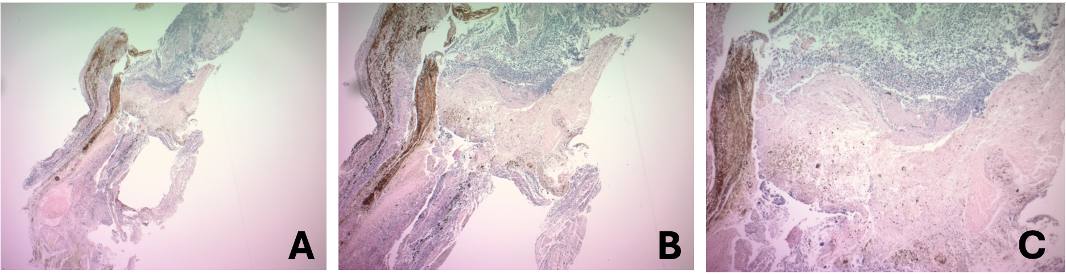

Figure: Figure 2. Necrotic Material, Acute Inflammatory infiltrate and brown pigment: the proximal esophagus biopsy shows necrotic material, acute inflammatory infiltrate and brown pigment; no viable tissue identified. Magnification 4x (A), 5x (B), and 10x (C).

Disclosures:

Bianca Thakkar indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Rachael Hagen indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Courtney Stead indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Maria Gorgan indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Martin Hoffman indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Bianca Thakkar, DO1, Rachael Hagen, DO1, Courtney Stead, MD2, Maria Gorgan, MD3, Martin Hoffman, DO3. P0725 - Acute Esophageal Necrosis in a Critically Ill Patient: A Rare and Lethal Cause of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1University of Connecticut Health, Farmington, CT; 2University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT; 3Saint Francis Hospital, Trinity Health of New England, Hartford, CT

Introduction: Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), also known as “black esophagus,” is a rare, life-threatening condition characterized by diffuse circumferential black discoloration of the esophageal mucosa, typically affecting the distal esophagus with a sharp demarcation at the gastroesophageal junction. AEN is most often associated with a combination of ischemic insult, gastric acid reflux, and impaired mucosal defenses, typically in the context of systemic illness, hemodynamic instability, or multiorgan failure.

Case Description/

Methods: A 77-year-old female with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease presented with acute altered mental status, coffee-ground emesis, and signs of hemodynamic compromise. She was hypotensive, hypothermic, and in early septic shock, with labs notable for leukocytosis, anemia, elevated lactate (16 mmol/L), and acute kidney injury. Imaging revealed a cirrhotic-appearing liver with ascites and a large hiatal hernia with esophageal dilation. Her hospital course was complicated by hypoxic respiratory failure, worsening renal function, and melena requiring multiple transfusions and vasopressor support. She was empirically treated for variceal bleeding with an octreotide drip. Upper endoscopy revealed circumferential black discoloration of the esophagus consistent with AEN. Biopsies confirmed mucosal necrosis. Despite aggressive supportive care, her condition deteriorated, and after goals-of-care discussions, she was transitioned to comfort care and subsequently passed away.

Discussion: AEN remains a rare but critical diagnosis, often presenting with upper GI bleeding and occurring in elderly patients with significant comorbidities. The pathophysiology involves a synergistic combination of hypoperfusion, acid-mediated injury, and impaired mucosal repair. Diagnosis is confirmed via endoscopy and histopathology. Management is primarily supportive, emphasizing hemodynamic stabilization, PPI therapy, bowel rest, and addressing underlying causes. Mortality remains high, driven largely by the severity of associated systemic illness rather than the esophageal necrosis itself.

This case highlights the importance of considering AEN in critically ill patients presenting with GI bleeding and multiple comorbidities. Prompt recognition, supportive care, and early endoscopic evaluation are essential to guide management and prognostication.

Figure: Figure 1. Endoscopy (EGD) which shows upper third of the esophagus (A) and middle third of the esophagus (B), which appears grossly black, highly concerning for esophageal necrosis.

Figure: Figure 2. Necrotic Material, Acute Inflammatory infiltrate and brown pigment: the proximal esophagus biopsy shows necrotic material, acute inflammatory infiltrate and brown pigment; no viable tissue identified. Magnification 4x (A), 5x (B), and 10x (C).

Disclosures:

Bianca Thakkar indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Rachael Hagen indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Courtney Stead indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Maria Gorgan indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Martin Hoffman indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Bianca Thakkar, DO1, Rachael Hagen, DO1, Courtney Stead, MD2, Maria Gorgan, MD3, Martin Hoffman, DO3. P0725 - Acute Esophageal Necrosis in a Critically Ill Patient: A Rare and Lethal Cause of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.