Sunday Poster Session

Category: Biliary/Pancreas

P0070 - Acid Suppression and Pancreatitis: Are PCABs Safer Than PPIs?

Sunday, October 26, 2025

3:30 PM - 7:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

- VS

Venkata Sunkesula, MD

Case Western Reserve University / MetroHealth

Cleveland, OH

Presenting Author(s)

Venkata Sunkesula, MD1, Thai Hau Koo, MD2, Rishi Chowdhary, MD1, Archana Kharel, MD3, Sirisha kundrapu, MD1, Ala Abdel-Jalil, MD1

1Case Western Reserve University / MetroHealth, Cleveland, OH; 2University of Sciences Malaysia Specialist Hospital, Kelantan, Kelantan, Malaysia; 3Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH

Introduction: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are widely used and generally safe, though rare associations with acute pancreatitis (AP) have been reported. Potassium-competitive acid blockers (PCABs) offer more potent acid suppression, but their safety profile remains less defined. This study compares the incidence and severity of new-onset AP following PCAB vs. PPI initiation in a large real-world cohort.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study used the TriNetX database, comprising over 275 million de-identified patient records from 134 healthcare organizations across 14 countries. Adults (≥18 years) who received a prescription for a PCAB or PPI between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2024, were included. Exclusions were prior acute or chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic neoplasms, organ transplantation, or pregnancy. PCAB users were excluded if they had PPI exposure in the prior 6 months. Propensity score matching (1:1) adjusted for demographics and known pancreatitis risk factors (alcohol use, gallstones, obesity, diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, and pancreatitis-associated medications). Kaplan-Meier survival curves and univariate Cox models assessed the 90-day incidence of acute pancreatitis. Subgroup analyses were stratified by age and severity.

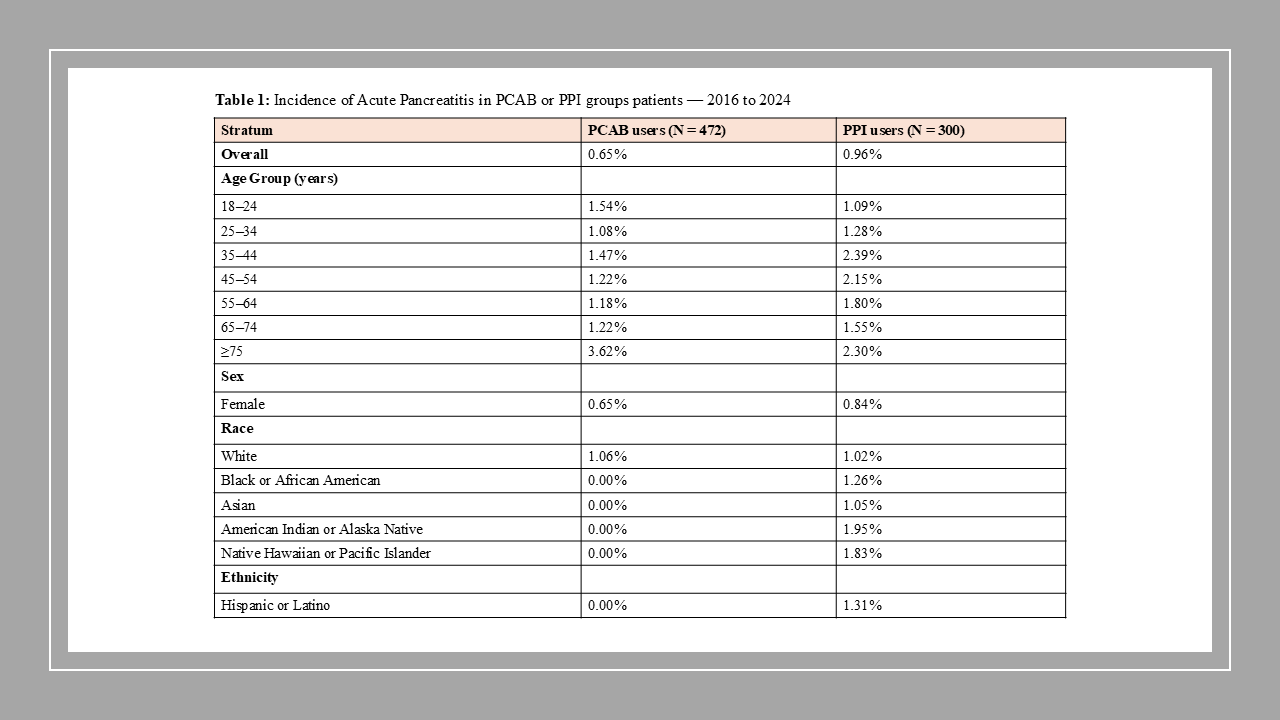

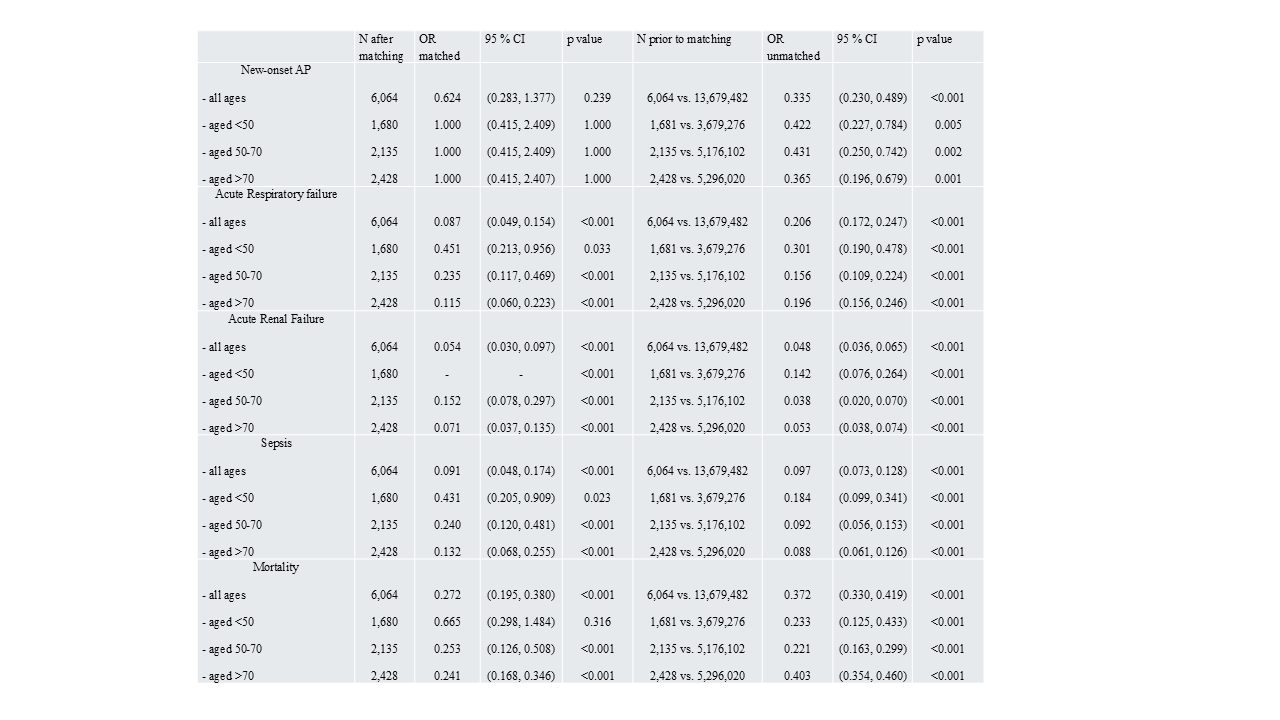

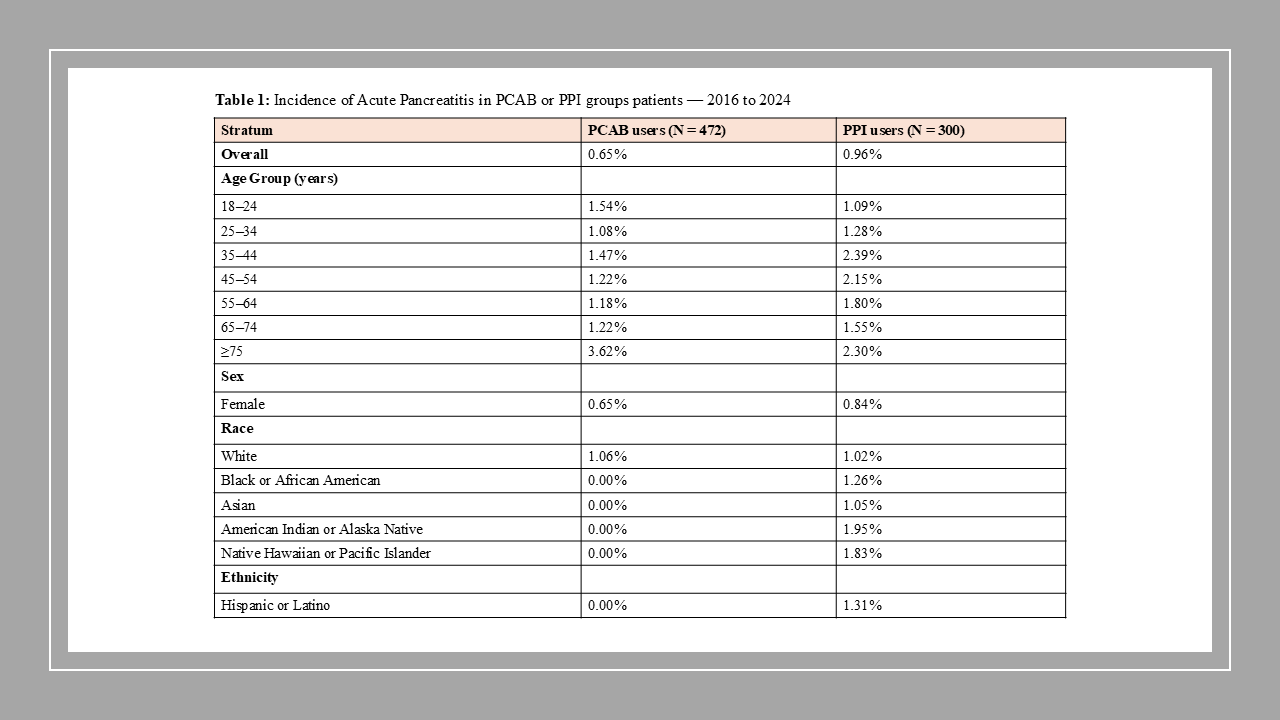

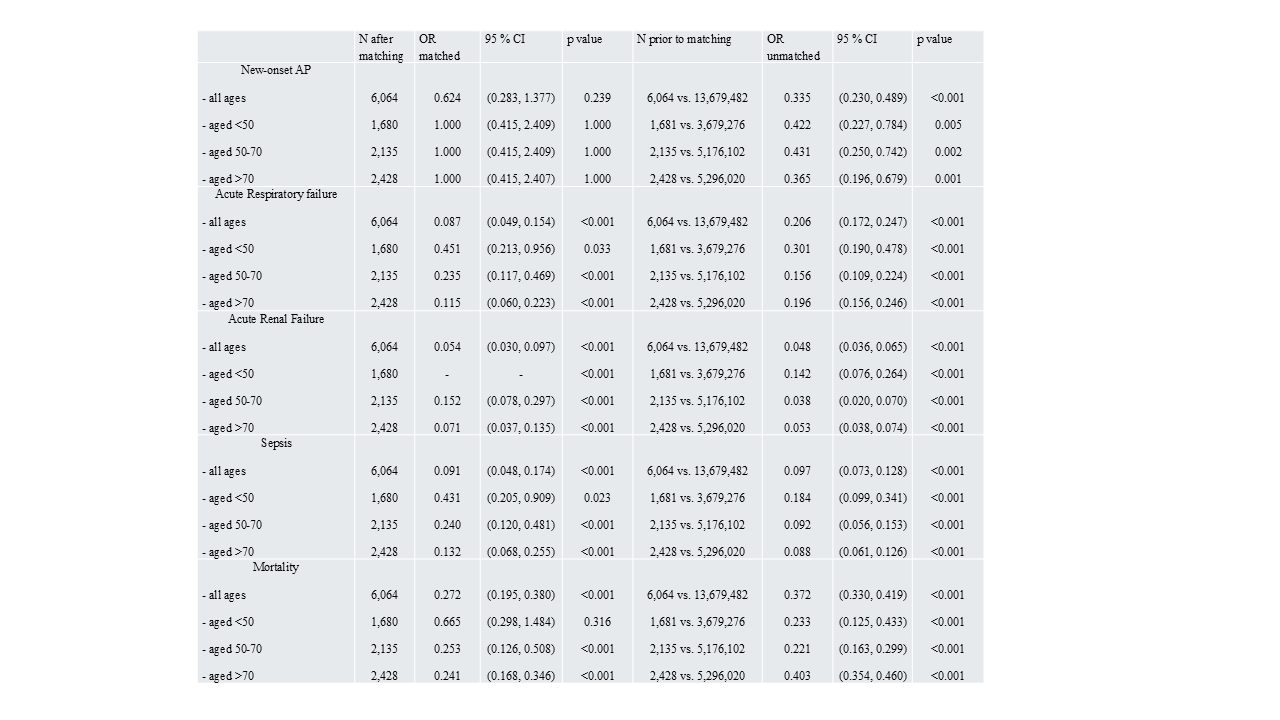

Results: We included 77,841 PCAB users and 13,497,134 PPI users. Within 90 days of therapy initiation, AP developed in 0.65% of the PCAB group and 0.96% of the PPI group, with higher rates in patients ≥75 years (PCAB: 3.62%; PPI: 2.30%) and females. After propensity score matching, PCABs were not significantly associated with reduced odds of new-onset AP (OR 0.624; 95% CI 0.283–1.377; p=0.239), with no significant differences in age-stratified analyses. However, PCAB use was associated with significantly lower odds of acute respiratory failure (OR 0.087), renal failure (OR 0.054), sepsis (OR 0.091), and mortality (OR 0.272) compared to PPIs (all p < 0.001). These associations were strongest in patients >70 years.

Discussion: In this large, matched cohort study, PCAB use was associated with significantly lower odds of acute respiratory failure, renal failure, sepsis, and mortality compared to PPIs. The benefits were most pronounced in patients aged 50 and older, particularly for respiratory failure and mortality. These findings support the potential clinical advantage of PCABs over PPIs, especially in high-risk populations. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these associations.

Figure: Table 1: Incidence of Acute Pancreatitis in PCAB or PPI groups patients — 2016 to 2024

Figure: Table 2: Odds ratios* of clinical outcome of patients with Acute Pancreatitis among those with PCAB as compared to PPI within first 90 days follow up

Disclosures:

Venkata Sunkesula indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Thai Hau Koo indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Rishi Chowdhary indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Archana Kharel indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sirisha kundrapu indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Ala Abdel-Jalil indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Venkata Sunkesula, MD1, Thai Hau Koo, MD2, Rishi Chowdhary, MD1, Archana Kharel, MD3, Sirisha kundrapu, MD1, Ala Abdel-Jalil, MD1. P0070 - Acid Suppression and Pancreatitis: Are PCABs Safer Than PPIs?, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1Case Western Reserve University / MetroHealth, Cleveland, OH; 2University of Sciences Malaysia Specialist Hospital, Kelantan, Kelantan, Malaysia; 3Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH

Introduction: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are widely used and generally safe, though rare associations with acute pancreatitis (AP) have been reported. Potassium-competitive acid blockers (PCABs) offer more potent acid suppression, but their safety profile remains less defined. This study compares the incidence and severity of new-onset AP following PCAB vs. PPI initiation in a large real-world cohort.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study used the TriNetX database, comprising over 275 million de-identified patient records from 134 healthcare organizations across 14 countries. Adults (≥18 years) who received a prescription for a PCAB or PPI between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2024, were included. Exclusions were prior acute or chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic neoplasms, organ transplantation, or pregnancy. PCAB users were excluded if they had PPI exposure in the prior 6 months. Propensity score matching (1:1) adjusted for demographics and known pancreatitis risk factors (alcohol use, gallstones, obesity, diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, and pancreatitis-associated medications). Kaplan-Meier survival curves and univariate Cox models assessed the 90-day incidence of acute pancreatitis. Subgroup analyses were stratified by age and severity.

Results: We included 77,841 PCAB users and 13,497,134 PPI users. Within 90 days of therapy initiation, AP developed in 0.65% of the PCAB group and 0.96% of the PPI group, with higher rates in patients ≥75 years (PCAB: 3.62%; PPI: 2.30%) and females. After propensity score matching, PCABs were not significantly associated with reduced odds of new-onset AP (OR 0.624; 95% CI 0.283–1.377; p=0.239), with no significant differences in age-stratified analyses. However, PCAB use was associated with significantly lower odds of acute respiratory failure (OR 0.087), renal failure (OR 0.054), sepsis (OR 0.091), and mortality (OR 0.272) compared to PPIs (all p < 0.001). These associations were strongest in patients >70 years.

Discussion: In this large, matched cohort study, PCAB use was associated with significantly lower odds of acute respiratory failure, renal failure, sepsis, and mortality compared to PPIs. The benefits were most pronounced in patients aged 50 and older, particularly for respiratory failure and mortality. These findings support the potential clinical advantage of PCABs over PPIs, especially in high-risk populations. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these associations.

Figure: Table 1: Incidence of Acute Pancreatitis in PCAB or PPI groups patients — 2016 to 2024

Figure: Table 2: Odds ratios* of clinical outcome of patients with Acute Pancreatitis among those with PCAB as compared to PPI within first 90 days follow up

Disclosures:

Venkata Sunkesula indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Thai Hau Koo indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Rishi Chowdhary indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Archana Kharel indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sirisha kundrapu indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Ala Abdel-Jalil indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Venkata Sunkesula, MD1, Thai Hau Koo, MD2, Rishi Chowdhary, MD1, Archana Kharel, MD3, Sirisha kundrapu, MD1, Ala Abdel-Jalil, MD1. P0070 - Acid Suppression and Pancreatitis: Are PCABs Safer Than PPIs?, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.