Tuesday Poster Session

Category: Biliary/Pancreas

P4508 - High Seas and Hidden Bleeds: Post-Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Hemosuccus Pancreaticus in a Cruise Passenger

Tuesday, October 28, 2025

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Jahnavi Udaikumar, MD (she/her/hers)

NYU Langone Health

Brooklyn, NY

Presenting Author(s)

Jahnavi Udaikumar, MD1, Carlos Echeverria, MD1, Daniel Marino, MD, MBA2, Adam Goodman, MD3

1NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, New York, NY; 2NYU Langone Health, New York, NY; 3NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, New York, NY

Introduction: Hemosuccus pancreaticus (HP) is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, occurring in fewer than 1 in 1,500 cases. It involves bleeding into the pancreatic duct, commonly from arterial pseudoaneurysms due to chronic pancreatitis, though the differential is broad and trauma and vascular anomalies should also be considered. Diagnosis is difficult due to intermittent bleeding, vague symptoms, and complex anatomy. The full triad—epigastric pain, GI bleeding, and hyperamylasemia—is rare. Contrast-enhanced CT and angiography aid diagnosis; embolization is first-line treatment. We report a challenging case of HP post-cardiac arrest, managed with empiric embolization.

Case Description/

Methods: A 78-year-old female with atrial fibrillation (on rivaroxaban) suffered a cardiac arrest due to arrhythmia while aboard a cruise ship. She was resuscitated, intubated, stabilized with vasopressors, and transferred to a tertiary center. Initial evaluation revealed acute respiratory failure with lactic acidosis, acute kidney injury, hyperkalemia, and shock liver. Notably, the patient was found to have elevated lipase, although pancreatitis was not present on imaging. She was managed with corticosteroids, antibiotics, and continuous renal replacement therapy in the ICU with gradual neurologic improvement by day 14.

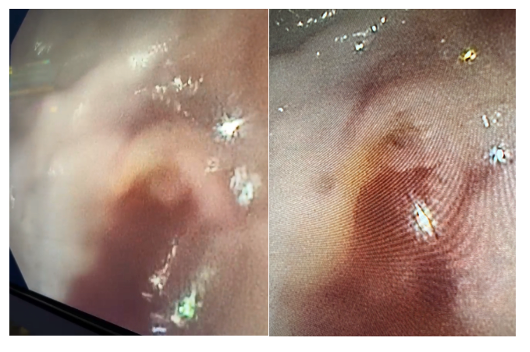

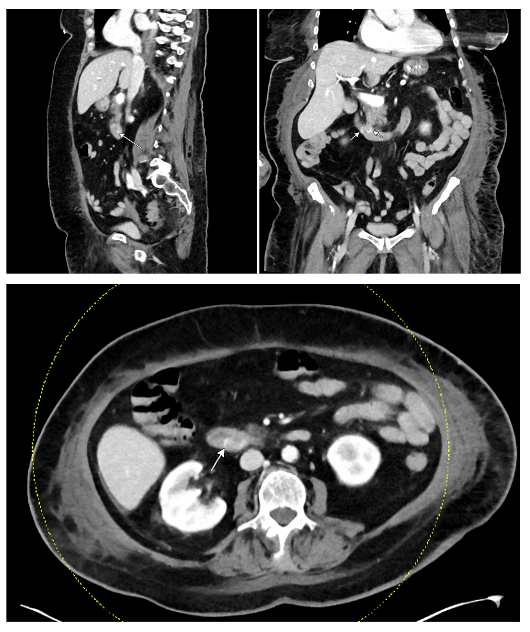

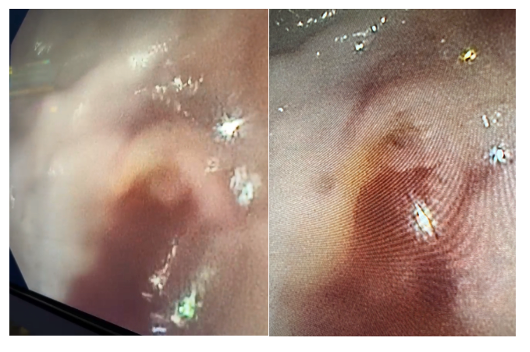

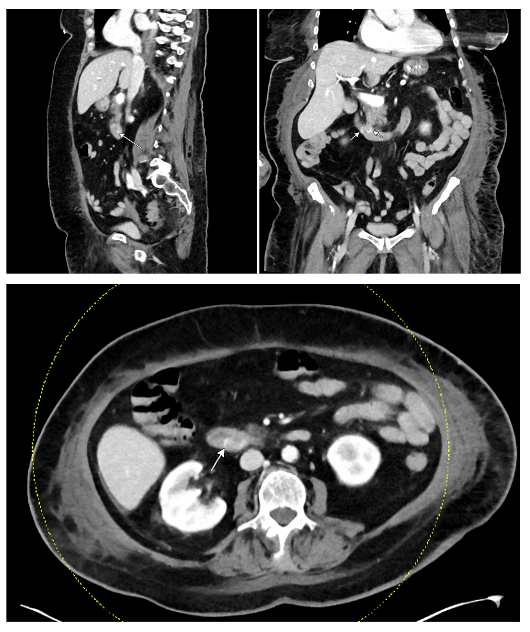

Prior to extubation, she developed melena and anemia, despite no prior history of pancreatitis or abdominal pain. Forward-viewing endoscopy showed active bleeding at the ampulla of Vater, and side-viewing duodenoscopy confirmed blood from the pancreatic duct, consistent with HP (Figure 1). Although no pseudoaneurysm was visualized, CT angiography later demonstrated extravasation near the ampulla, leading to empiric coil embolization of the gastroduodenal artery (Figure 2). Ultimately, the patient stabilized prior to repatriation.

Discussion: This case underscores the diagnostic complexity of HP, particularly in the absence of classic risk factors or clinical features. Post-CPR trauma and anticoagulation likely contributed to HP. Diagnosis was aided by timely imaging and the use of a side-viewing endoscope, which excluded hemobilia. Despite intervention, bleeding can persist in up to 20% of cases. Although rare, HP should remain on the differential diagnosis of ampullary GI bleeds, particularly following trauma or critical illness. Early recognition is essential for favorable outcomes.

Figure: Figure 1: Endoscopic visualization of bleeding from pancreatic orifice

Figure: Figure 2: CTA indicating foci of hyperenhancement within the duodenum in the ampullary region on the venous phase, no active GI bleed in arterial phase, no pseudoaneurysm but presence of mild peripancreatic fat stranding

Disclosures:

Jahnavi Udaikumar indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Carlos Echeverria indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Daniel Marino indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Adam Goodman: Ambu, Inc – Advisor or Review Panel Member. Boston Scientific – Advisor or Review Panel Member. Iterative Health – Advisor or Review Panel Member.

Jahnavi Udaikumar, MD1, Carlos Echeverria, MD1, Daniel Marino, MD, MBA2, Adam Goodman, MD3. P4508 - High Seas and Hidden Bleeds: Post-Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Hemosuccus Pancreaticus in a Cruise Passenger, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, New York, NY; 2NYU Langone Health, New York, NY; 3NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, New York, NY

Introduction: Hemosuccus pancreaticus (HP) is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, occurring in fewer than 1 in 1,500 cases. It involves bleeding into the pancreatic duct, commonly from arterial pseudoaneurysms due to chronic pancreatitis, though the differential is broad and trauma and vascular anomalies should also be considered. Diagnosis is difficult due to intermittent bleeding, vague symptoms, and complex anatomy. The full triad—epigastric pain, GI bleeding, and hyperamylasemia—is rare. Contrast-enhanced CT and angiography aid diagnosis; embolization is first-line treatment. We report a challenging case of HP post-cardiac arrest, managed with empiric embolization.

Case Description/

Methods: A 78-year-old female with atrial fibrillation (on rivaroxaban) suffered a cardiac arrest due to arrhythmia while aboard a cruise ship. She was resuscitated, intubated, stabilized with vasopressors, and transferred to a tertiary center. Initial evaluation revealed acute respiratory failure with lactic acidosis, acute kidney injury, hyperkalemia, and shock liver. Notably, the patient was found to have elevated lipase, although pancreatitis was not present on imaging. She was managed with corticosteroids, antibiotics, and continuous renal replacement therapy in the ICU with gradual neurologic improvement by day 14.

Prior to extubation, she developed melena and anemia, despite no prior history of pancreatitis or abdominal pain. Forward-viewing endoscopy showed active bleeding at the ampulla of Vater, and side-viewing duodenoscopy confirmed blood from the pancreatic duct, consistent with HP (Figure 1). Although no pseudoaneurysm was visualized, CT angiography later demonstrated extravasation near the ampulla, leading to empiric coil embolization of the gastroduodenal artery (Figure 2). Ultimately, the patient stabilized prior to repatriation.

Discussion: This case underscores the diagnostic complexity of HP, particularly in the absence of classic risk factors or clinical features. Post-CPR trauma and anticoagulation likely contributed to HP. Diagnosis was aided by timely imaging and the use of a side-viewing endoscope, which excluded hemobilia. Despite intervention, bleeding can persist in up to 20% of cases. Although rare, HP should remain on the differential diagnosis of ampullary GI bleeds, particularly following trauma or critical illness. Early recognition is essential for favorable outcomes.

Figure: Figure 1: Endoscopic visualization of bleeding from pancreatic orifice

Figure: Figure 2: CTA indicating foci of hyperenhancement within the duodenum in the ampullary region on the venous phase, no active GI bleed in arterial phase, no pseudoaneurysm but presence of mild peripancreatic fat stranding

Disclosures:

Jahnavi Udaikumar indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Carlos Echeverria indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Daniel Marino indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Adam Goodman: Ambu, Inc – Advisor or Review Panel Member. Boston Scientific – Advisor or Review Panel Member. Iterative Health – Advisor or Review Panel Member.

Jahnavi Udaikumar, MD1, Carlos Echeverria, MD1, Daniel Marino, MD, MBA2, Adam Goodman, MD3. P4508 - High Seas and Hidden Bleeds: Post-Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Hemosuccus Pancreaticus in a Cruise Passenger, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.