Sunday Poster Session

Category: GI Bleeding

P0968 - Black Esophagus: A Unique Cause of Hematemesis

Sunday, October 26, 2025

3:30 PM - 7:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

Kevin Vallejo, MD

HCA Florida Healthcare

Miami, FL

Presenting Author(s)

Kevin Vallejo, MD1, Charles Vallejo, DO2, Jasmin Cabrera-Luis, MD1, Yanie Oliva, MD3

1HCA Florida Healthcare, Miami, FL; 2Florida Atlantic University Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Boca Raton, FL; 3HCA Florida Healthcare, Doral, FL

Introduction: Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), aka “black esophagus”, is an extremely rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with reported incidence as low as 0.06%. It is typically diagnosed during emergency EGD, characterized by diffuse, circumferential black epithelia with sharp demarcation at the gastroesophageal junction. Patients may present with dysphagia, nausea, hematemesis, epigastric pain, and syncope. Common risk factors described are alcohol use disorder, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and those in hemodynamic compromise, such as sepsis, shock, or multiorgan failure. Management includes maintaining the patient nil-per-os (NPO), hemodynamic stabilization, IV proton pump inhibitors (PPI), and correcting the precipitating factor. Below we present the case of a 72-year-old female who presented with AEN.

Case Description/

Methods: A 72-year-old female with a PMHx of alcohol use disorder presented after being found down by her neighbor with blood around her mouth. She was transferred to the ER where she had a witnessed 1L hematemesis, subsequently aspirated, and was emergently intubated for airway protection. Broad spectrum antibiotics were initiated for concern of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). She was started on high dose norepinephrine drip and octreotide drip, when she then developed ventricular fibrillation and was cardioverted twice. CT of the abdomen demonstrated severe fatty liver disease and pancreatitis. Her initial hemoglobin was 11 g/dL which dropped to 6 g/dL; she was given massive transfusion protocol. She was started on pantoprazole drip and taken to the ICU where emergent bedside EGD demonstrated diffuse necrosis throughout the esophagus, consistent with AEN. Despite aggressive measures, our patient expired on hospital day 3.

Discussion: While AEN is a rare cause of hematemesis, clinicians must remain alert and initiate management immediately. AEN management includes aggressive hemodynamic resuscitation, IV PPI therapy, and treatment of underlying processes. Common complications include esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and death, with a reported mortality ranging from 12.5% to 32% of all patients, although this is typically related to the underlying condition causing AEN rather than AEN itself. Following resolution of the acute critical illness, most patients experience resolution of necrosis with conservative management, with up to 25% developing esophageal strictures which may require repeated endoscopic dilations.

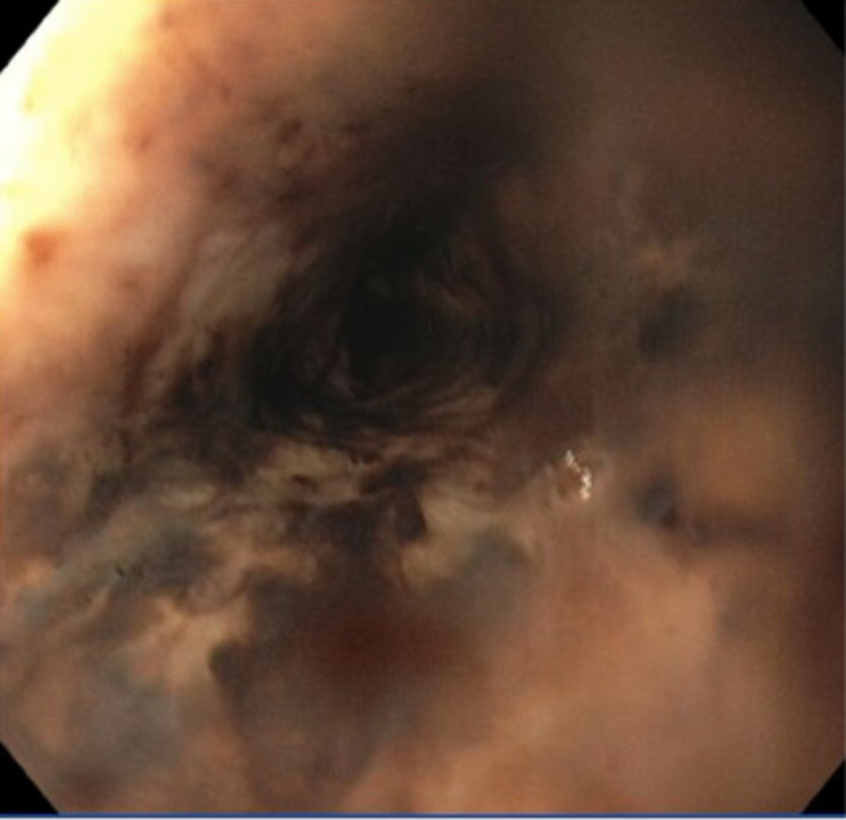

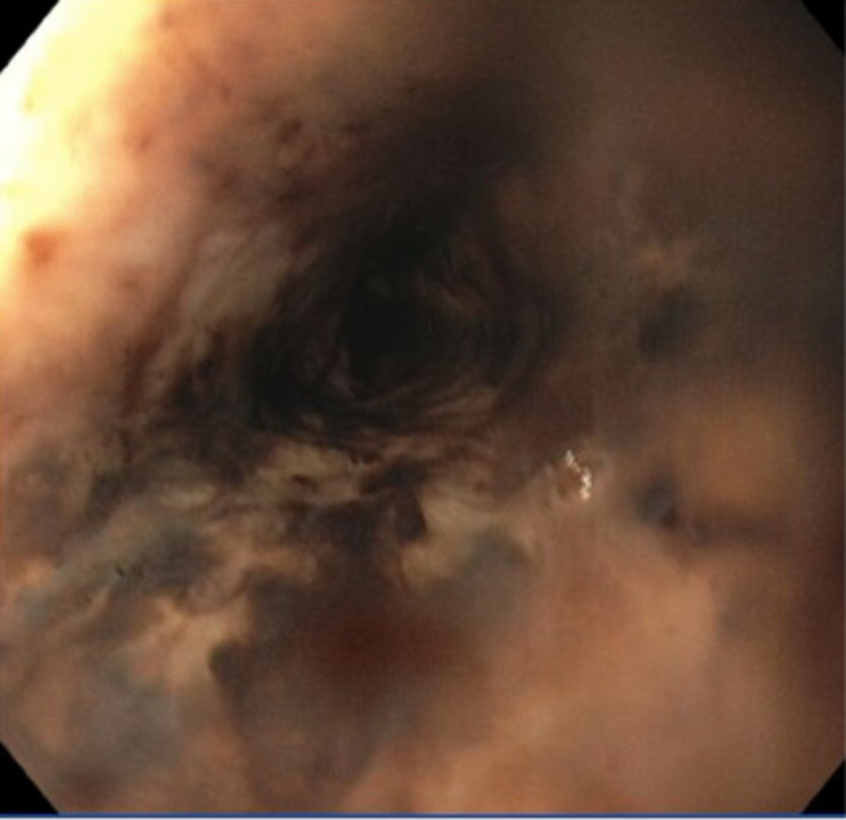

Figure: EGD demonstrating circumferential esophageal necrosis

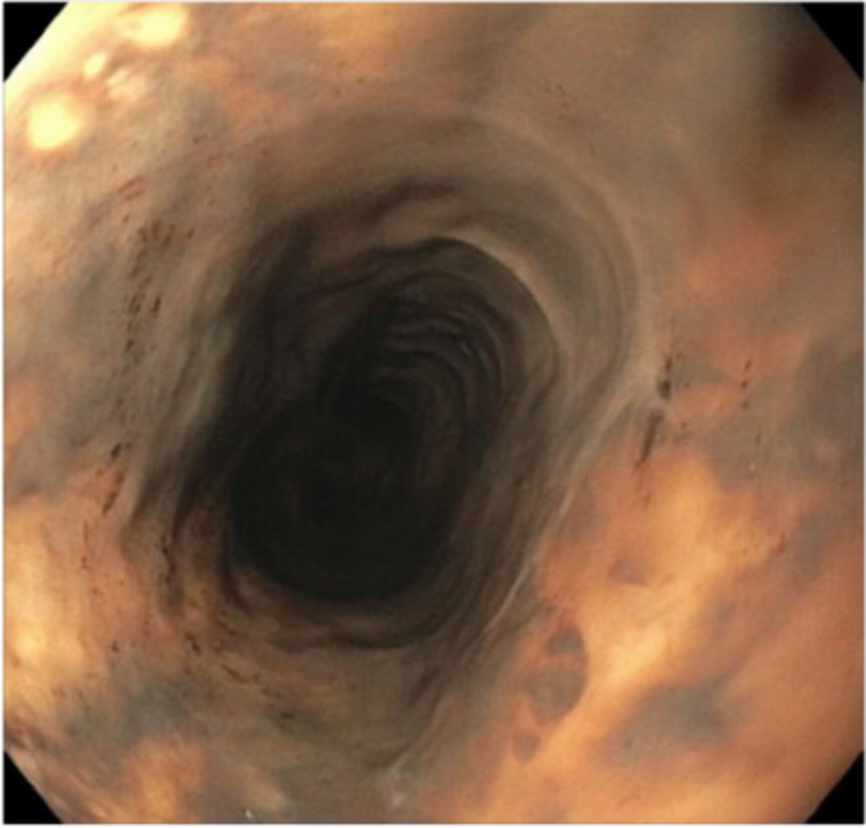

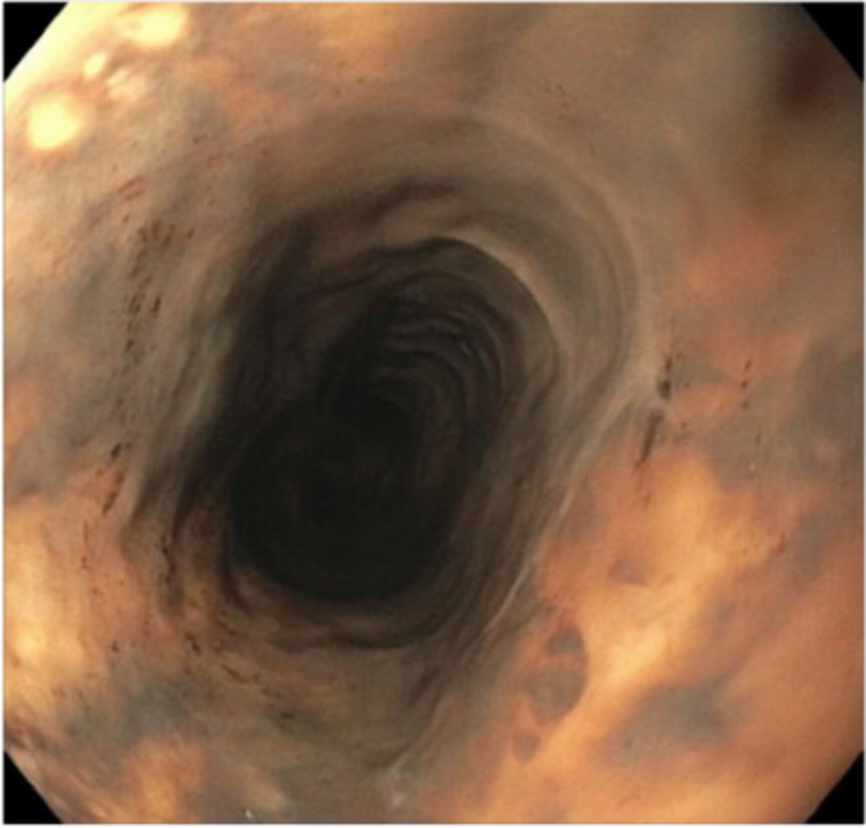

Figure: EGD demonstrating necrotic mucosa consistent with AEN

Disclosures:

Kevin Vallejo indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Charles Vallejo indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Jasmin Cabrera-Luis indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Yanie Oliva indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Kevin Vallejo, MD1, Charles Vallejo, DO2, Jasmin Cabrera-Luis, MD1, Yanie Oliva, MD3. P0968 - Black Esophagus: A Unique Cause of Hematemesis, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1HCA Florida Healthcare, Miami, FL; 2Florida Atlantic University Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Boca Raton, FL; 3HCA Florida Healthcare, Doral, FL

Introduction: Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), aka “black esophagus”, is an extremely rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with reported incidence as low as 0.06%. It is typically diagnosed during emergency EGD, characterized by diffuse, circumferential black epithelia with sharp demarcation at the gastroesophageal junction. Patients may present with dysphagia, nausea, hematemesis, epigastric pain, and syncope. Common risk factors described are alcohol use disorder, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and those in hemodynamic compromise, such as sepsis, shock, or multiorgan failure. Management includes maintaining the patient nil-per-os (NPO), hemodynamic stabilization, IV proton pump inhibitors (PPI), and correcting the precipitating factor. Below we present the case of a 72-year-old female who presented with AEN.

Case Description/

Methods: A 72-year-old female with a PMHx of alcohol use disorder presented after being found down by her neighbor with blood around her mouth. She was transferred to the ER where she had a witnessed 1L hematemesis, subsequently aspirated, and was emergently intubated for airway protection. Broad spectrum antibiotics were initiated for concern of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). She was started on high dose norepinephrine drip and octreotide drip, when she then developed ventricular fibrillation and was cardioverted twice. CT of the abdomen demonstrated severe fatty liver disease and pancreatitis. Her initial hemoglobin was 11 g/dL which dropped to 6 g/dL; she was given massive transfusion protocol. She was started on pantoprazole drip and taken to the ICU where emergent bedside EGD demonstrated diffuse necrosis throughout the esophagus, consistent with AEN. Despite aggressive measures, our patient expired on hospital day 3.

Discussion: While AEN is a rare cause of hematemesis, clinicians must remain alert and initiate management immediately. AEN management includes aggressive hemodynamic resuscitation, IV PPI therapy, and treatment of underlying processes. Common complications include esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and death, with a reported mortality ranging from 12.5% to 32% of all patients, although this is typically related to the underlying condition causing AEN rather than AEN itself. Following resolution of the acute critical illness, most patients experience resolution of necrosis with conservative management, with up to 25% developing esophageal strictures which may require repeated endoscopic dilations.

Figure: EGD demonstrating circumferential esophageal necrosis

Figure: EGD demonstrating necrotic mucosa consistent with AEN

Disclosures:

Kevin Vallejo indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Charles Vallejo indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Jasmin Cabrera-Luis indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Yanie Oliva indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Kevin Vallejo, MD1, Charles Vallejo, DO2, Jasmin Cabrera-Luis, MD1, Yanie Oliva, MD3. P0968 - Black Esophagus: A Unique Cause of Hematemesis, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.