Monday Poster Session

Category: Liver

P3963 - The Silent Infiltrator: Sarcoidosis Progressing to Cirrhosis

Monday, October 27, 2025

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

- GD

Gerardo Diaz Garcia, DO

University of Florida College of Medicine - 655 W 8th St Jacksonville, FL 32221UNITED STATES - Jacksonville, FL

Jacksonville, FL

Presenting Author(s)

Gerardo Diaz Garcia, DO1, Nadim Qadir, DO2, Anvit Reddy, DO1, Yasasvhinie Santharam, DO2, Sneh Parekh, DO2, Pramod Reddy, MD2

1University of Florida College of Medicine - 655 W 8th St Jacksonville, FL 32221UNITED STATES - Jacksonville, FL, Jacksonville, FL; 2University of Florida College of Medicine, Jacksonville, FL

Introduction: Although hepatic involvement is a known manifestation of sarcoidosis, progression to cirrhosis is uncommon. Hepatic involvement—defined by abnormal liver enzymes, imaging findings, or histopathology—is seen in approximately 6–30% of systemic sarcoidosis cases, though most are asymptomatic or non-progressive. Clinically significant complications, such as cirrhosis and portal hypertension, occur in a minority of patients. The pathogenesis is thought to involve chronic granulomatous inflammation, granulomatous phlebitis, and secondary ischemic injury. When cirrhosis develops, it carries substantial morbidity and mortality, with gastrointestinal bleeding and hepatic failure being common. Treatments like TIPS and variceal banding have shown limited efficacy in these cases. We present a case of hepatic sarcoidosis progressing to end-stage liver disease, emphasizing this rare but serious complication.

Case Description/

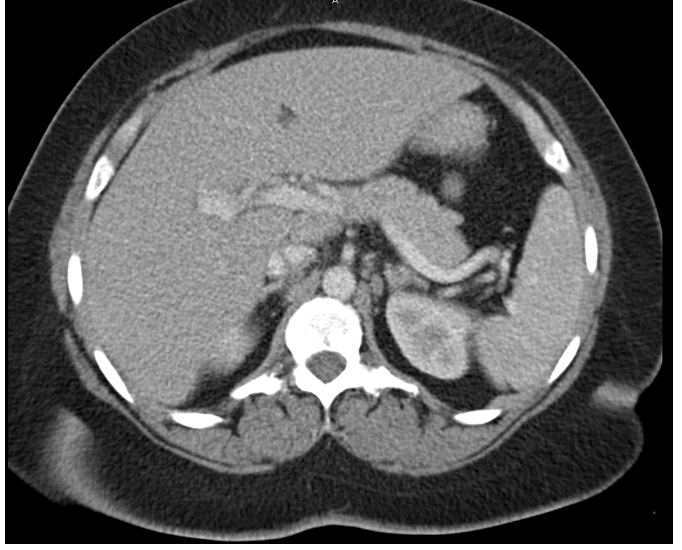

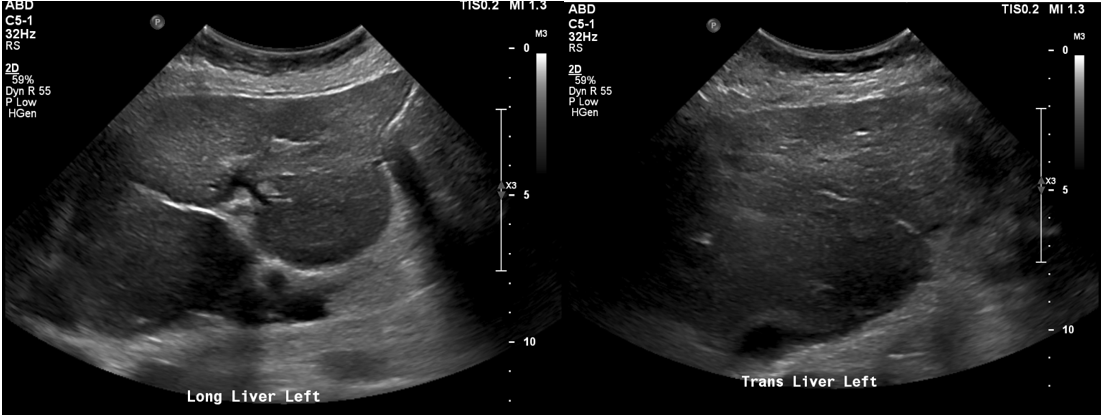

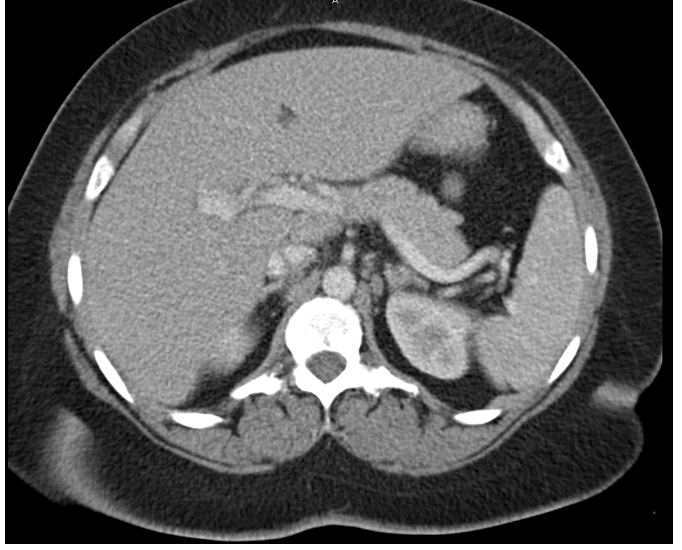

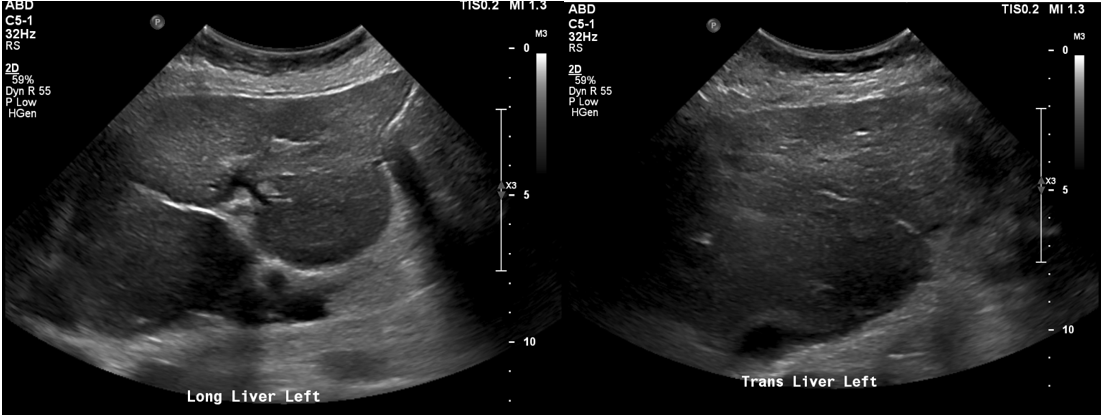

Methods: A 43-year-old African American woman initially presented to the hospital with complaints of progressive dysphagia, weight loss, chronic cough, and low-grade fevers. Lab work was significant for an elevated AST at 57 U/L, INR of 1.2, and hemoglobin of 8.4 g/dL. CT Chest revealed mediastinal lymphadenopathy, bilateral ground-glass opacities, and hepatomegaly [figure 1]. Bronchoscopy with lymph node biopsy showed non-caseating granulomas consistent with stage I–II pulmonary sarcoidosis. A liver biopsy also demonstrated non-caseating granulomas, confirming hepatic involvement. She was diagnosed with sarcoidosis and started on prednisone 40 mg daily, with close outpatient follow-up. Seven years later, she returned with abdominal pain and swelling. She was diagnosed with cirrhosis and admitted for evaluation, including paracentesis and thoracentesis. Records from a recent outside hospital confirmed prior esophageal variceal banding. Imaging showed bilateral pleural effusions, mild pericardial effusion, and cirrhotic liver morphology on US [figure 2]. Findings consistent with decompensated liver disease secondary to hepatic sarcoidosis.

Discussion: This case highlights how chronic liver involvement in sarcoidosis can quietly advance to fibrosis and, ultimately, cirrhosis—even in the absence of clear symptoms. In patients without common risk factors for liver disease, sarcoidosis should remain on the differential. Timely recognition, consistent follow-up, and early management may help slow progression and improve patient outcomes in this uncommon yet significant complication.

Figure: Figure 1. Initial CT Scan demonstrating enlarged liver consistent with hepatomegaly.

Figure: Figure 2. RUQ US showing heterogeneous appearance of the liver and coarsened echotexture as seen in chronic liver disease.

Disclosures:

Gerardo Diaz Garcia indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Nadim Qadir indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Anvit Reddy indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Yasasvhinie Santharam indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sneh Parekh indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Pramod Reddy indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Gerardo Diaz Garcia, DO1, Nadim Qadir, DO2, Anvit Reddy, DO1, Yasasvhinie Santharam, DO2, Sneh Parekh, DO2, Pramod Reddy, MD2. P3963 - The Silent Infiltrator: Sarcoidosis Progressing to Cirrhosis, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1University of Florida College of Medicine - 655 W 8th St Jacksonville, FL 32221UNITED STATES - Jacksonville, FL, Jacksonville, FL; 2University of Florida College of Medicine, Jacksonville, FL

Introduction: Although hepatic involvement is a known manifestation of sarcoidosis, progression to cirrhosis is uncommon. Hepatic involvement—defined by abnormal liver enzymes, imaging findings, or histopathology—is seen in approximately 6–30% of systemic sarcoidosis cases, though most are asymptomatic or non-progressive. Clinically significant complications, such as cirrhosis and portal hypertension, occur in a minority of patients. The pathogenesis is thought to involve chronic granulomatous inflammation, granulomatous phlebitis, and secondary ischemic injury. When cirrhosis develops, it carries substantial morbidity and mortality, with gastrointestinal bleeding and hepatic failure being common. Treatments like TIPS and variceal banding have shown limited efficacy in these cases. We present a case of hepatic sarcoidosis progressing to end-stage liver disease, emphasizing this rare but serious complication.

Case Description/

Methods: A 43-year-old African American woman initially presented to the hospital with complaints of progressive dysphagia, weight loss, chronic cough, and low-grade fevers. Lab work was significant for an elevated AST at 57 U/L, INR of 1.2, and hemoglobin of 8.4 g/dL. CT Chest revealed mediastinal lymphadenopathy, bilateral ground-glass opacities, and hepatomegaly [figure 1]. Bronchoscopy with lymph node biopsy showed non-caseating granulomas consistent with stage I–II pulmonary sarcoidosis. A liver biopsy also demonstrated non-caseating granulomas, confirming hepatic involvement. She was diagnosed with sarcoidosis and started on prednisone 40 mg daily, with close outpatient follow-up. Seven years later, she returned with abdominal pain and swelling. She was diagnosed with cirrhosis and admitted for evaluation, including paracentesis and thoracentesis. Records from a recent outside hospital confirmed prior esophageal variceal banding. Imaging showed bilateral pleural effusions, mild pericardial effusion, and cirrhotic liver morphology on US [figure 2]. Findings consistent with decompensated liver disease secondary to hepatic sarcoidosis.

Discussion: This case highlights how chronic liver involvement in sarcoidosis can quietly advance to fibrosis and, ultimately, cirrhosis—even in the absence of clear symptoms. In patients without common risk factors for liver disease, sarcoidosis should remain on the differential. Timely recognition, consistent follow-up, and early management may help slow progression and improve patient outcomes in this uncommon yet significant complication.

Figure: Figure 1. Initial CT Scan demonstrating enlarged liver consistent with hepatomegaly.

Figure: Figure 2. RUQ US showing heterogeneous appearance of the liver and coarsened echotexture as seen in chronic liver disease.

Disclosures:

Gerardo Diaz Garcia indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Nadim Qadir indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Anvit Reddy indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Yasasvhinie Santharam indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sneh Parekh indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Pramod Reddy indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Gerardo Diaz Garcia, DO1, Nadim Qadir, DO2, Anvit Reddy, DO1, Yasasvhinie Santharam, DO2, Sneh Parekh, DO2, Pramod Reddy, MD2. P3963 - The Silent Infiltrator: Sarcoidosis Progressing to Cirrhosis, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.