Tuesday Poster Session

Category: GI Bleeding

P5273 - Metastatic Melanoma: An Unexpected Cause of Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Tuesday, October 28, 2025

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

.jpeg.jpg)

Pitambar Khanal, MBBS (he/him/his)

Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital

Royal Oak, MI

Presenting Author(s)

Pitambar Khanal, MBBS1, Samiksha Pandey, MD2, Aiden Van Loo, MD1, Maryconi M.. Jacob, MD1

1Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital, Royal Oak, MI; 2Corewellhealth William Beaumont University Hospital, Royal Oak, MI

Introduction: Malignant melanoma is the most common tumor to metastasize to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Only 1–5% of patients develop clinically apparent GI symptoms, which are often nonspecific—such as abdominal pain, anemia, GI bleeding, or bowel obstruction—mimicking other GI disorders and making diagnosis challenging. We present a case of malignant melanoma in a patient who initially presented with abdominal pain and was subsequently found to have GI metastasis.

Case Description/

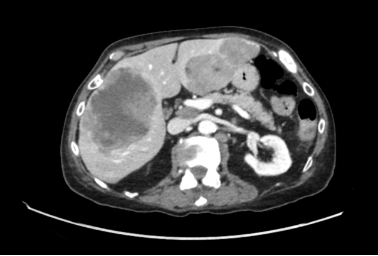

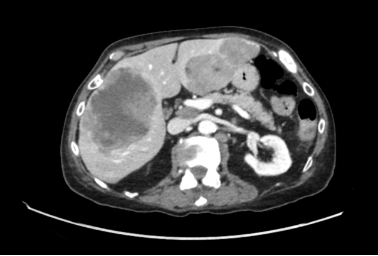

Methods: An 80-year-old male presented with a three-week history of epigastric pain. One year earlier, he had been diagnosed with Stage IIB (pT3bN0Mx) superficial spreading cutaneous melanoma of the lower back, measuring 3.5 mm in Breslow depth with ulceration. He underwent wide local excision with a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. At this presentation, lab showed hemoglobin 9 g/dL, bilirubin 3 mg/dL, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 234 IU/L. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated multifocal metastases involving the liver, left adrenal gland, and retroperitoneum (Figure A). The small bowel appeared unremarkable on imaging. During hospitalization, the patient developed melena, prompting an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which revealed a 15 × 15 mm deep, cratered ulcer with heaped-up margins in the second portion of the duodenum (Figure B). Biopsy of the lesion confirmed metastatic melanoma, with tumor cells positive for SOX10 and S100 on immunohistochemistry.

Discussion: GI metastases from melanoma often present as ulcerated nodules or masses and may lead to significant morbidity. Although imaging modalities are valuable for identifying metastatic disease, endoscopic evaluation remains crucial for direct visualization and tissue diagnosis. Histologic confirmation relies on immunohistochemical markers such as S100, SOX10, and HMB-45, which are highly sensitive. In cases of bleeding from metastatic ulcers, endoscopic therapies—including epinephrine injection, topical hemostatic agents, and argon plasma coagulation—can provide temporary hemostasis. However, their effectiveness is often limited due to the friable and vascular nature of malignant tissue. Early recognition and diagnosis are essential, as prompt initiation of immunotherapy or targeted therapy can improve survival in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for GI involvement in patients with a history of melanoma, especially in the setting of nonspecific abdominal symptoms or GI bleeding.

Figure: Figure A: Multifocal metastatic lesions in the liver

Figure: Figure B: Metastatic ulcer in the 2nd part of the duodenum

Disclosures:

Pitambar Khanal indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Samiksha Pandey indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Aiden Van Loo indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Maryconi Jacob indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Pitambar Khanal, MBBS1, Samiksha Pandey, MD2, Aiden Van Loo, MD1, Maryconi M.. Jacob, MD1. P5273 - Metastatic Melanoma: An Unexpected Cause of Gastrointestinal Bleeding, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital, Royal Oak, MI; 2Corewellhealth William Beaumont University Hospital, Royal Oak, MI

Introduction: Malignant melanoma is the most common tumor to metastasize to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Only 1–5% of patients develop clinically apparent GI symptoms, which are often nonspecific—such as abdominal pain, anemia, GI bleeding, or bowel obstruction—mimicking other GI disorders and making diagnosis challenging. We present a case of malignant melanoma in a patient who initially presented with abdominal pain and was subsequently found to have GI metastasis.

Case Description/

Methods: An 80-year-old male presented with a three-week history of epigastric pain. One year earlier, he had been diagnosed with Stage IIB (pT3bN0Mx) superficial spreading cutaneous melanoma of the lower back, measuring 3.5 mm in Breslow depth with ulceration. He underwent wide local excision with a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. At this presentation, lab showed hemoglobin 9 g/dL, bilirubin 3 mg/dL, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 234 IU/L. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated multifocal metastases involving the liver, left adrenal gland, and retroperitoneum (Figure A). The small bowel appeared unremarkable on imaging. During hospitalization, the patient developed melena, prompting an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which revealed a 15 × 15 mm deep, cratered ulcer with heaped-up margins in the second portion of the duodenum (Figure B). Biopsy of the lesion confirmed metastatic melanoma, with tumor cells positive for SOX10 and S100 on immunohistochemistry.

Discussion: GI metastases from melanoma often present as ulcerated nodules or masses and may lead to significant morbidity. Although imaging modalities are valuable for identifying metastatic disease, endoscopic evaluation remains crucial for direct visualization and tissue diagnosis. Histologic confirmation relies on immunohistochemical markers such as S100, SOX10, and HMB-45, which are highly sensitive. In cases of bleeding from metastatic ulcers, endoscopic therapies—including epinephrine injection, topical hemostatic agents, and argon plasma coagulation—can provide temporary hemostasis. However, their effectiveness is often limited due to the friable and vascular nature of malignant tissue. Early recognition and diagnosis are essential, as prompt initiation of immunotherapy or targeted therapy can improve survival in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for GI involvement in patients with a history of melanoma, especially in the setting of nonspecific abdominal symptoms or GI bleeding.

Figure: Figure A: Multifocal metastatic lesions in the liver

Figure: Figure B: Metastatic ulcer in the 2nd part of the duodenum

Disclosures:

Pitambar Khanal indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Samiksha Pandey indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Aiden Van Loo indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Maryconi Jacob indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Pitambar Khanal, MBBS1, Samiksha Pandey, MD2, Aiden Van Loo, MD1, Maryconi M.. Jacob, MD1. P5273 - Metastatic Melanoma: An Unexpected Cause of Gastrointestinal Bleeding, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.