Monday Poster Session

Category: Esophagus

P2874 - Black Esophagus in Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Rare Intersection of Metabolic Derangement and GI Catastrophe

Monday, October 27, 2025

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM PDT

Location: Exhibit Hall

- NM

Nancy Mayer, DO

Riverside Medical Center

Bourbonnais, IL

Presenting Author(s)

Nancy Mayer, DO1, Charles Swanson, DO1, Matthew Kaplan, DO2

1Riverside Medical Center, Bourbonnais, IL; 2Digestive Disease Consultants, Bourbonnais, IL

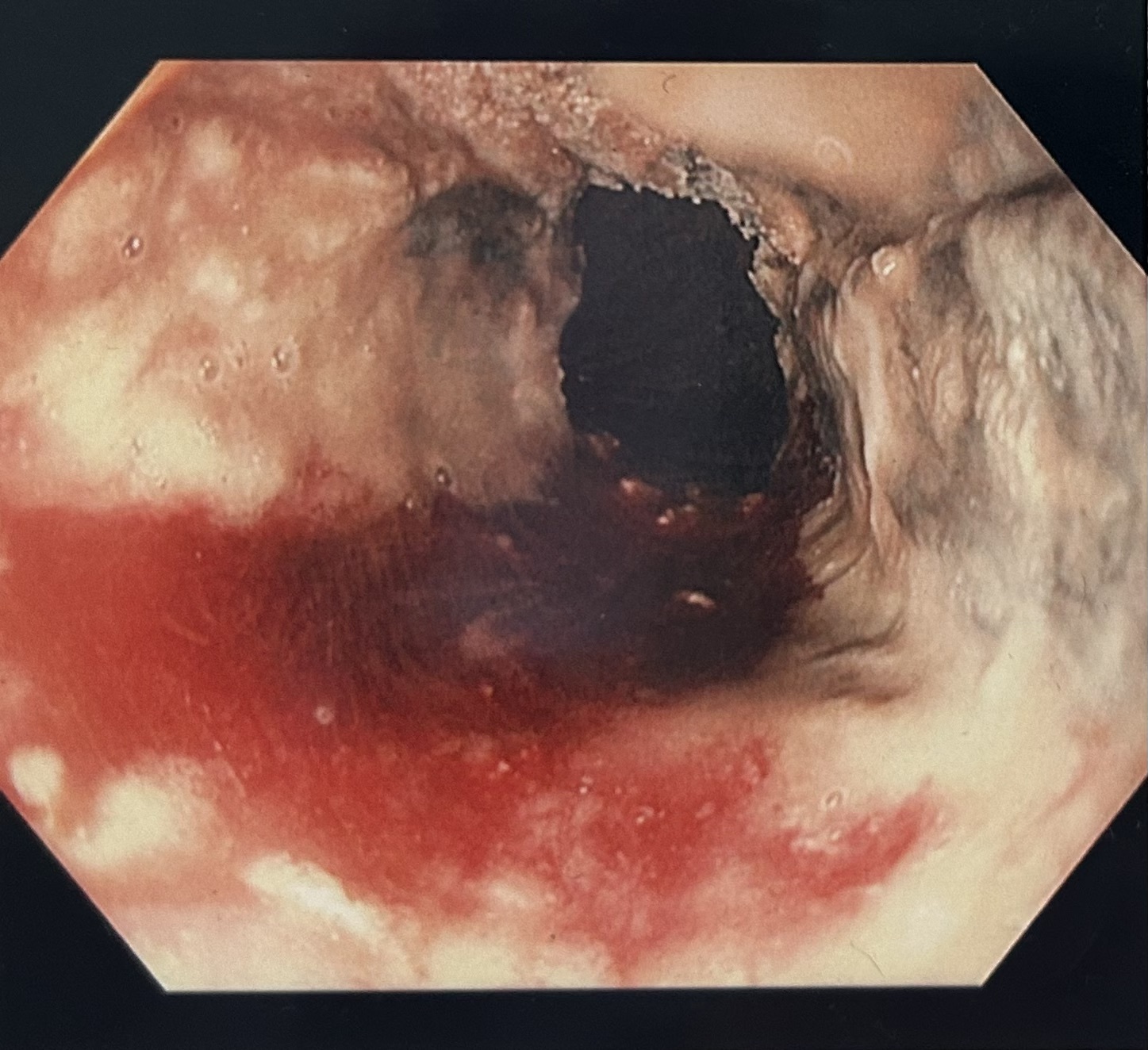

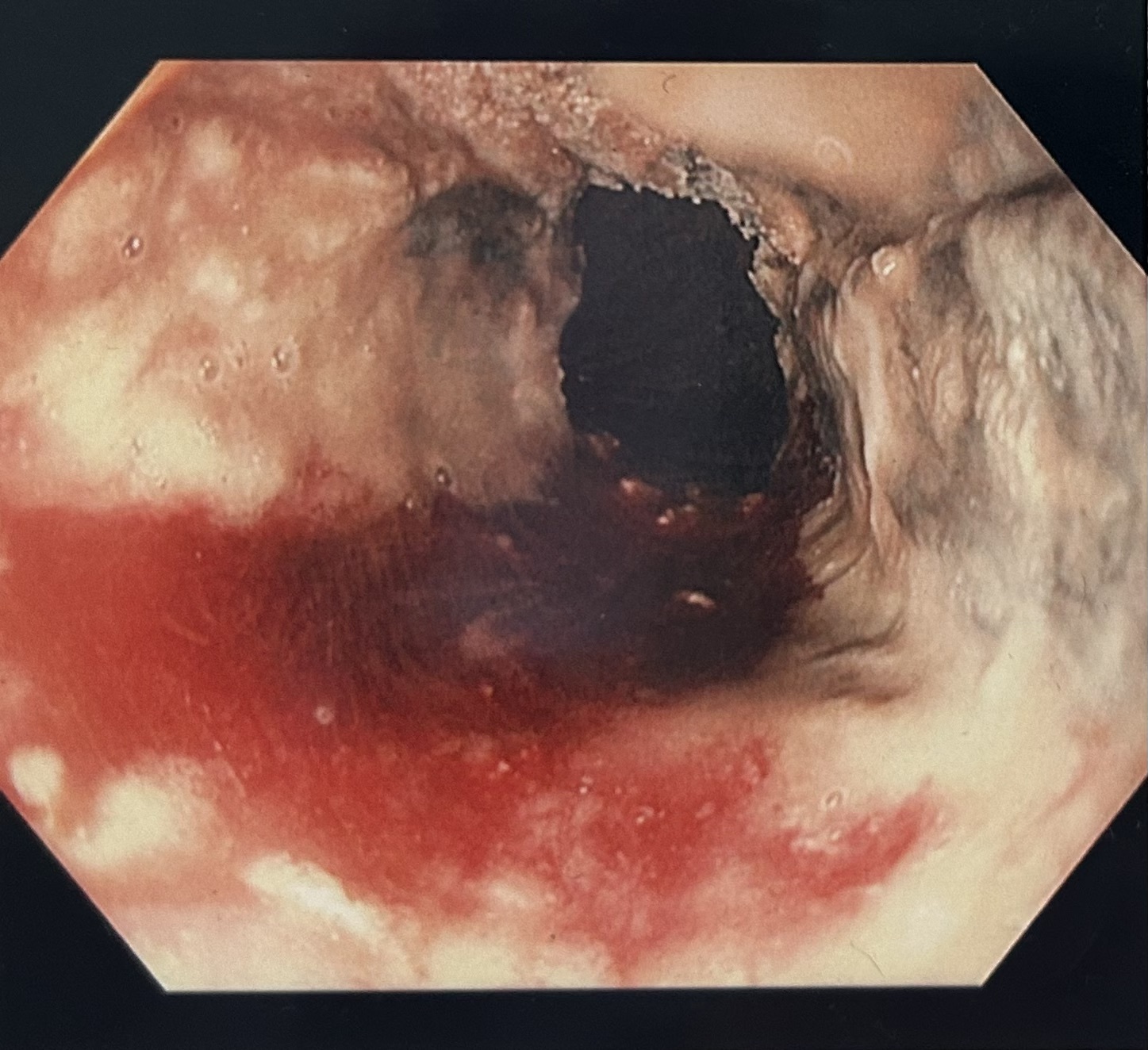

Introduction: Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), or “black esophagus,” is a rare, potentially life-threatening cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, characterized by circumferential black discoloration of the esophageal mucosa visualized on endoscopy. Though uncommon, AEN has been associated with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), where profound metabolic derangements and hemodynamic compromise contribute to mucosal injury.

Case Description/

Methods: A 64-year-old male with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented after a fall due to generalized weakness. Laboratory work reveled a glucose of 627, bicarbonate of 8, and pH of 6.9, indicating severe DKA. CT brain was unremarkable. However, the patient’s mentation deteriorated, necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation. He progressed to shock state requiring three vasopressors and stress dose steroids. An insulin infusion, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and aggressive IV fluids were started for suspected septic shock-induced DKA. Soon after, dark red output from the orogastric tube raised concern for upper GI bleeding and hemorrhagic shock. The patient received pRBC transfusions and a pantoprazole infusion. Urgent bedside endoscopy revealed a dark pigmented esophagus with friable, ulcerated mucosa and active oozing at the gastroesophageal junction. Hemostasis was achieved with epinephrine injections, bipolar cautery, and hemostatic powder. Hemoglobin levels stabilized post-EGD with no further bleeding. Within 48 hours, vasopressors were weaned off, and the patient was successfully extubated.

Discussion: AEN is a rare, potentially fatal cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with mortality rates as high as 32%, and incidence reported to range between 0.01% to 0.28% of patient’s undergoing upper endoscopy.1 Due to its rarity, the exact mechanisms remain uncertain. Most theories favor a multifactorial etiology, involving local hypoperfusion, mucosal barrier loss, and gastric acid reflux leading to tissue necrosis. Proposed mechanisms by which DKA causes AEN include poor glycemic control accelerating atherosclerosis, osmotic diuresis causing hypovolemia and low-flow states, and gastric stasis increasing reflux-related mucosal injury.2 Management focuses on treating the underlying cause while providing supportive care. Hemodynamic stabilization and treatment of DKA are central to therapy. While AEN carries a poor prognosis, many patients recover with appropriate management, highlighting the importance of vigilance in at-risk populations.

Figure: Dark pigmented esophagus with friable, ulcerated mucosa consistent with AEN

Disclosures:

Nancy Mayer indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Charles Swanson indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Matthew Kaplan indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Nancy Mayer, DO1, Charles Swanson, DO1, Matthew Kaplan, DO2. P2874 - Black Esophagus in Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Rare Intersection of Metabolic Derangement and GI Catastrophe, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.

1Riverside Medical Center, Bourbonnais, IL; 2Digestive Disease Consultants, Bourbonnais, IL

Introduction: Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), or “black esophagus,” is a rare, potentially life-threatening cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, characterized by circumferential black discoloration of the esophageal mucosa visualized on endoscopy. Though uncommon, AEN has been associated with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), where profound metabolic derangements and hemodynamic compromise contribute to mucosal injury.

Case Description/

Methods: A 64-year-old male with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented after a fall due to generalized weakness. Laboratory work reveled a glucose of 627, bicarbonate of 8, and pH of 6.9, indicating severe DKA. CT brain was unremarkable. However, the patient’s mentation deteriorated, necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation. He progressed to shock state requiring three vasopressors and stress dose steroids. An insulin infusion, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and aggressive IV fluids were started for suspected septic shock-induced DKA. Soon after, dark red output from the orogastric tube raised concern for upper GI bleeding and hemorrhagic shock. The patient received pRBC transfusions and a pantoprazole infusion. Urgent bedside endoscopy revealed a dark pigmented esophagus with friable, ulcerated mucosa and active oozing at the gastroesophageal junction. Hemostasis was achieved with epinephrine injections, bipolar cautery, and hemostatic powder. Hemoglobin levels stabilized post-EGD with no further bleeding. Within 48 hours, vasopressors were weaned off, and the patient was successfully extubated.

Discussion: AEN is a rare, potentially fatal cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with mortality rates as high as 32%, and incidence reported to range between 0.01% to 0.28% of patient’s undergoing upper endoscopy.1 Due to its rarity, the exact mechanisms remain uncertain. Most theories favor a multifactorial etiology, involving local hypoperfusion, mucosal barrier loss, and gastric acid reflux leading to tissue necrosis. Proposed mechanisms by which DKA causes AEN include poor glycemic control accelerating atherosclerosis, osmotic diuresis causing hypovolemia and low-flow states, and gastric stasis increasing reflux-related mucosal injury.2 Management focuses on treating the underlying cause while providing supportive care. Hemodynamic stabilization and treatment of DKA are central to therapy. While AEN carries a poor prognosis, many patients recover with appropriate management, highlighting the importance of vigilance in at-risk populations.

Figure: Dark pigmented esophagus with friable, ulcerated mucosa consistent with AEN

Disclosures:

Nancy Mayer indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Charles Swanson indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Matthew Kaplan indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Nancy Mayer, DO1, Charles Swanson, DO1, Matthew Kaplan, DO2. P2874 - Black Esophagus in Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Rare Intersection of Metabolic Derangement and GI Catastrophe, ACG 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Phoenix, AZ: American College of Gastroenterology.